Nuclear Planet: the NPT and Covid-19

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which this year celebrates the 50th anniversary of its entry into force, has had its five-year review conference postponed for the first time in its history. This is not the only major diplomatic event that cannot be held this Spring. The postponement of the tenth NPT Review Conference comes with its share of hesitations, uncertainties and other issues. One of them is whether it can be useful.

The decision to postpone and the options ahead

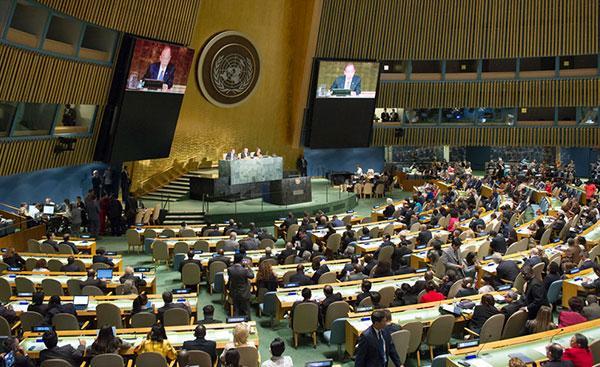

Scheduled since spring 2019 to be held at the United Nations headquarters in New York from 27 April to 22 May 2020, the tenth five-year NPT Review Conference was officially postponed sine die on 27 March. The president-designate of the Conference, Ambassador Gustavo Zlauvinen of Argentina, began consultations on options for postponement in early March, according to an interview with Arms Control TodaySee Daryl G. Kimball, “NPT Review Conference Postponed”, Arms Control Today, April 2020.. An initial proposal to delegations on 13 March to suspend the conference by holding a procedural meeting on the opening day, 27 April, was abandoned. The idea was to symbolically mark the date, elect a Conference bureau and perhaps agree on a work programme. But the worsening health situation in the world, and particularly in New York, and the partial closure of UN headquarters on 16 March, indicated that such a minimal option was no longer tenable. The option of a virtual inaugural session was also considered and then abandoned, particularly in view of the disparity in States' capacities to participate effectively. On 25 March, a proposal was made to the NPT regional groups to postpone the event “as soon as circumstances permit, but no later than April 2021”See the letter from President Zlauvinen, 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, 27 mars 2020..

In his letter of 13 March, President Zlauvinen was keen “to assure States Parties that [he] will undertake all efforts, in coordination with the Secretariat, to ensure that the Review Conference is held as soon as possible and that it is able to undertake its important mandate”. For the record, NPT Review Conferences are agreed among States parties to the Treaty and on their own resources. The same applies to the organization of the five-year review process in the framework of the Preparatory Commissions and through a consultative mechanism conducted by the Bureau of the Conference. Decisions should be taken by consensus or tacit agreement.

Among the various options that were proposed during the month of March as the pandemic was gaining in importance, the option of a meeting limited in duration and volume was not selected. In particular, the President of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) argued that “given the central importance of the NPT as an essential pillar of international security, the NPT Review Conference is not an event whose duration and/or number of participants can be limited”Tariq Rauf, “Postpone the NPT Review Conference to 2021 and Convene in Vienna”, InDepthNews, 16 March 2020.. That the 191 states parties to the NPT can participate in the NPT Review Conference cannot be questioned. The participation rate is generally high: 153 States Parties participated in the 2005 conferenceReview Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, Final Document, Part I, Organization of the work of the Conference, NPT/CONF.2005/57, p. 6., 172 States Parties were present at the 2010 conference2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, Final Document, Part I, vol. 1, NPT/CONF.2015/50 (vol. 1), p. 39., and 161 States Parties at the 2015 conference2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, Final Document, Part I, Organization and Work of the Conference, NPT/CONF.2015/50, p. 10.. At most, States could be asked for an expression of interest and an intention to be present in advance in the preparation of the conference this year or next year. On the other hand, a reduction in the size of delegations is no doubt conceivable, if necessary, in a conference space that would be constrained by specific health security measures. Finally, another option for reducing the size could impact on the representation and activity of civil society at the event, a risk which is not well regarded by many States Parties and is unlikely to be endorsed by the Presidency. As for the limitation of the conference in time, this is a recurring theme in the NPT review process on which many proposals have been made in the past and will be made again at the next conference. Theoretically, health circumstances could push the presidency to make a first attempt at reduction, on an exceptional or pilot basis. In practice, the modalities of such a reduction applied to the scheduling of the four weeks of meetings would probably be difficult to agree on in a consensual manner in the coming months without the possibility of a meeting of the Bureau of the Conference.

Some of the attentive observers of the NPT review cycle have become somewhat impatient with the time taken in March to act on the postponement decision. In reality, the reaction of the entire institutional mechanism was not overly slow. The time taken to formalize a temporary solution for the time being was due to two main factors. Firstly, there was a difficulty in agreeing among the 191 States Parties to the Treaty on a postponement date. Some states would like a postponement until the end of 2020. Others, including the 120 states of the NAM, recommend postponement for a full year, to April and May 2021. It is still too early to prejudge what will be concluded, but a second factor could come into play: to date, the scheduling of diplomatic meetings at the United Nations after the Summer of 2020 is such - including because of the postponement of events in the spring and no doubt in the summer - that holding the NPT Review Conference is likely to be a logistical challenge, if the meeting is held in New York at all.

With regard to the postponement date, autumn 2020, winter 2020/2021 or spring 2021 are three possible options. The final choice should depend mainly on health and logistical factors. In this respect, autumn 2020 seems a little too close in the calendar. Moreover, the year following the holding of a Review Conference marking a pause in the five-year process, the first preparatory commission for the 2021 - 2025 cycle will not be held before 2022. As such, the Tenth conference could therefore very well take place at the beginning of 2021 - between January and May - without upsetting the programming of the new cycle, with a greater likelihood that the pandemic will be under control, and without risking disrupting the resumption of multilateral meetings that characterise the late summer and autumn in New York, Geneva and Vienna. On the other hand, the argument that the Covid-19 pandemic justifies holding the conference in 2021 in Vienna rather than New York is less convincingTariq Rauf, “Relentless Spread of Coronavirus Obliges Postponing of 2020 NPT Review to 2021”, Atomic Reporters, 11 mars 2020.. Admittedly, nothing in the Treaty obliges the states parties to hold the Review Conference in New YorkFor the record, the NPT is very flexible on this issue. Article 8 paragraph 3 provides that “Five years after the entry into force of this Treaty, a Conference of the Parties to the Treaty shall be held in Geneva, Switzerland”. Moreover, the convening of five-yearly review conferences of the Treaty is a discretion left to the Parties, but not an obligation.. However, New York is the city with the largest number of States Parties’ representations to the NPT; Vienna is an important centre for nuclear diplomacy (IAEA, CTBTO) but the United Nations headquarters is the symbolic level that is appropriate for an NPT Review Conference; finally, New York is not a capital, whereas Vienna is the capital of a State whose positions on nuclear matters are not very consensual.

At the time of this writing, January 2021 in New York appears to be the option chosen by the presidency of the Conference subject to acceptance by all regional groups. This option remains to be confirmed before the summer. The month of January 2021 does not present a clear conflict of agendas. For the record, it will be a significant moment in Russia and the United States: in the orthodox calendar, Christmas and New Year's Day are celebrated in the first half of January; 20 January will also be the date on which the next President of the United States takes office; 5 February will mark the end of the application of the New START Treaty by the United States and Russia. Barring any surprises, these events should not determine the outcome of the conference. They will, however, impact on the climate of the meeting and are likely to direct observations and comments towards the strategic bilateral US-Russian relationship. Naturally, a change in the White House could be accompanied by announcements likely to break with the positions of the previous administration, that could influence the outcome of the conference (Iran nuclear file, strategic dialogue with Russia, arms control treaties, etc.).

In essence, the decision to postpone itself, the timing of the postponement and, finally, the place of the postponement cannot be taken for granted: reputed to be the cornerstone of the international nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament regime, the NPT has been based on its review rhythm set in stone, if not since 1975, then at least since 1995, when the Treaty was extended indefinitely, as the parties were given latitude in the text concluded in 1968Article 10, paragraph 2. (another anniversary this year, incidentally, than the 25 years of the landmark 1995 Review Conference). Since then, a review cycle has consisted of a blank year, directly following the year of the Conference, followed by three years to prepare in three successive Preparatory Commissions for the next Review Conference. These commissions are traditionally held in Vienna, Geneva and New York. For the first time since 1970, the current review cycle is interrupted; postponement scenarios are open; the highly uncertain progression of a pandemic remains, directly and indirectly, the main factor in reaching a decision. Under these conditions, how can we imagine that the “marble cornerstone” that is the NPT can easily be manipulated to be moved? The complexity of postponing the Tenth NPT Review Conference in time, or even space and time, is reminiscent of the complexity of “touching” the NPT as an instrument of international security. As such, the postponement of the conference itself can be seen as a metaphor for the crisis that the NPT has been going through for many years. However, if there is a crisis, the postponement may be an opportunity beyond the holding of the conference itself.

A treaty in crisis in a degraded environment

President Zlauvinen's letter of 27 March concludes with an encouragement: “In the interim, I encourage all States Parties to consider how they can work together to ensure success at the tenth NPT Review ConferenceOp. cit.”. Unfortunately, after the failure of the 2019 Preparatory Commission to provide the conference with a consensus document of recommendations, ensuring the success of the tenth NPT Review Conference is the main challenge already facing the States Parties to the Treaty this spring, for two complementary reasons.

The first is directly related to the international strategic environment. Indeed, this environment is so gloomy that the question of how to ensure the success of the future conference is not even addressed by analysts. Broadly speaking, the characteristics of the current strategic landscape that may negatively affect the conference are known: the re-emergence of power rivalries among several nuclear-weapon states, the stalled strategic bilateral arms control discipline, the worsening North Korean and Iranian proliferation crises, the near-suspension of the nuclear disarmament process, the deepening of regional sources of insecurity - particularly in the Middle East, the exacerbation of disagreements over the scope of the right to civil use (the fuel cycle), a less dynamic political approach to nuclear security, which is one of the few remaining consensual themes between nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear-weapon states. Combined and ramified, these characteristics are likely to affect the quality of the debates on the three pillars of the Treaty: non-proliferation, disarmament and peaceful uses.

The degraded nature of the strategic environment reinforces the crisis that the NPT seems to have been going through since the beginning of the century. This is the second reason why the 2020 Review Conference is risky. The 2005 Review Conference had already left an “impression of crisis” to observers: “NPT States Parties will have to (...) show imagination, initiative and firmness to demonstrate that the non-proliferation regime as it stands today is credible and that the impression of crisis was exaggerated and transitory. Failure to do so would put the NPT at serious risk of losing its substance at a time when it is particularly necessary for the preservation of international peace and securityEtienne de Gonneville, “La septième conférence d'examen du TNP - une étape dans une crise de régime?”, Annuaire français de relations internationales, La Documentation française/Bruylant, Volume VII, 2006.”. The following meeting was also unconvincing: “The 2010 conference is likely to go down in the history of the NPT as a milestone, because of the adoption by consensus of a balanced plan of action on the three pillars of the Treaty and because of the new efforts made in the practical implementation of the 1995 resolution on the Middle East. Beyond that, the instrument may no longer be the cornerstone of the global nuclear non-proliferation regimeBenjamin Hautecouverture, "The Eighth Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. What a success?", Annuaire français de relations internationales, La Documentation française/Bruylant, Volume XII, 2011..” Finally, the 2015 conference was perceived as a failure by all the protagonists in various ways: “Despite intensive consultations, the conference was unable to reach a final document in the absence of consensus. The polarization of discussions, at times clearly out of step with the strategic context, and the lack of agreement on the issue of the Middle East Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (NWFZ) prevented the adoption of a final document“Review Conferences 2015 and 2010”, France TNP (official website of the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs).”. The idea that the NPT is in crisis is not shared by all analysts. On the contrary, it can be argued that the Treaty remains the central element of the nuclear non-proliferation regime, that its success can be measured by the small number of states that have so far been successfully engaged in a military nuclear programme under the Treaty (Iranian attempt between 1999 and 2003) or after having left it (North Korea), that the mechanism is robust and should be assessed over time. However, apart from the fact that nuclear non-proliferation since the beginning of the century has been largely multifactorial and that the NPT's share in these factors may be open to debate, the NPT crisis could be no less real, precisely if one considers the long-time span (twenty to twenty-five years). If so, several factors would account for this:

- Naturally, a first factor could be identified in the strategic data that characterize the contemporary world. In detail, the bilateral rivalry between the United States and Russia, the emergence of China as a global power, the dissensions that are stirring up the P5 and the repercussions of these tensions on the disarmament process are weakening the NPT review process by exacerbating the traditional divide between the nuclear-weapon states and the non-nuclear-weapon states on the issue of disarmament at a time when the number of ratifications of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) is increasingAs of May 2020, the TPNW has 81 signatures and 37 ratifications. 50 ratifications are required for its entry into force.. The absence of a viable diplomatic solution to the North Korean and Iranian proliferation crises and the suspicion of military nuclear ambitions on the part of emerging regional powers risk undermining the historical authority of the non-proliferation norm. The perception of a diminishing risk of nuclear terrorism, the emergence of new questions regarding the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and a new dividing line between fuel and technology exporting and importing states may in various ways weaken the dynamism of the review of the civilian aspects of the Treaty (Article 4).

- A second factor would clearly be general technological developments, whether in nuclear armaments, conventional armaments, means of delivery, means of implementation of the Treaty (technologies related to civil uses, technologies related to verification, etc.). It could be argued that the NPT suffers from not being able to accommodate a technological reading of its provisions while the global technological environment impacts on the implementation of several key provisions of the Treaty (Article 3, Article 4, Article 6).

- A third factor could be identified in the relationship of the review process with regional issues and, in particular, the Middle East region since the adoption of the 1995 resolution on the Middle EastArticle 6 of the 1995 resolution on the Middle East which “commits all States Parties to the NPT” to the process of establishing a zone free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East.. The fundamental inadequacy of the NPT to deal with strategic Middle East disputes has contributed significantly to the weakening of the review process over the past twenty-five years. Indeed, many NPT actors share the perception that the inclusion of the Middle East issue in the review process has not been conducive to its effective treatment, while the 1995 resolution has somehow taken the Treaty hostage.

- A fourth crisis factor could relate more generally to the review mechanism itself, which seems unable to renew itself despite an increasingly shared perception of its inadequacies and dysfunctions. The four-week duration of the review conferences, the length of the final documents, the exhaustiveness criterion for reaching a consensus agreement (“nothing is concluded until everything is concluded”), the quantity of institutional and state documents (working documents, “non-papers”, state statements, regional group statements, statements of ad hoc coalitions, documentation from the conference bureau, etc.), the number of documents that have been produced by the review mechanism, and the number of documents that have not been made available to the public, the extreme formalisation of the institutional exercise compared to the place taken by informal negotiations orchestrated or not by the presidency have reduced, review cycle after review cycle, the effectiveness of the process. The readability of a conference has become accessible only to a public of very specialised observers, which is necessarily limited. This state of affairs has gradually paved the way for a simplification of the messages delivered at the end of the conferences, in the interest of a particular State or regional group or pressure group. For example, while the 2015 Review Conference is still remembered as a collective failure, it produced dynamic results that were very appreciable in terms of civil usesOne year before the last meeting in Washington of the cycle of nuclear security summits initiated by the Obama administration, the 2015 review conference was an opportunity to broaden the scope of this issue to all the parties to the NPT, to measure the efforts made and to record commitments on one of the consensual issues of Article 4, which was then undergoing strong development at the IAEA.. This success was drowned in a general perception of failure partly due to the thickness, opacity, and rigidity of the institutional sequence.

In sum, after having been successfully adapted and strengthened at the end of the Cold War, the NPT is probably going through a crisis of adaptation: it is no longer the dynamic instrument that it was between 1970 and 2000, both a chamber for recording profound changes in the strategic environment and a useful instrument for influencing the nuclear factor in inter-state security.

In these circumstances, it is difficult to see how a six-month postponement of the Tenth Review Conference of the Treaty to one year will change the outcome of the meeting. Firstly, the length of the postponement will not be sufficient to reverse the structural blocking factors. Secondly, although it is too early to draw strategic lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic, there is no evidence that power relations, of which the nuclear factor is an integral part, are taking advantage of the health crisis to relax. The Iranian and North Korean crises are not expected to progress towards their successful resolution by the winter of 2020/21. Finally, international health concerns are not conducive to nuclear diplomacy initiatives such as the adoption of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) by the United States and China, or the launch of negotiations on a treaty banning the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons (“Cut-off”), for example. At best, therefore, the challenges facing the NPT today will be suspended for the duration of the pandemic.

For the record, it can also be argued that the failure of the conference, an idea generally shared by the experts, is essentially unproven. The fact that a few official voices criticize the NPT on various grounds (ineffectiveness, discriminatory nature, etc.) should not obscure the fact that the vast majority of States Parties do not question either the spirit or the letter of the treaty. In the context of a rather acute crisis accentuated by the postponement itself, it may be that the Tenth Conference will be an opportunity for renewed and temporary cohesion between member states (besides, the fiftieth anniversary of the entry into force of the NPT will have been overshadowed by the Covid-19 pandemic).

Can the postponement be an opportunity?

The adjournment of the Tenth NPT Review Conference from six to nine months is a pause in the Treaty review process. This setback creates logistical, diplomatic and political challenges. At the strategic level, it is unlikely to change the fundamentals. However, rather than trying to find a way to save the meeting from a failure that everyone can anticipate at the multilateral diplomatic level, would it not be time to think about the crisis facing the NPT independently of the vicissitudes that accompany its review, and independently of ideas of failure or success? The fact that the NPT is in crisis does not imply that the instrument is inoperative. But its usefulness needs to be reassessed in the light of contemporary strategic issues.

Let us begin by dispelling the obsession with considering the adoption of a final document by consensus as the relevant sign of a conference's success. Only four of the nine NPT Review Conferences have achieved this result: in 1975, 1985, 2000, 2010. The most recent of these has not generated any collective momentum, other than a plan of action to which states continue to refer. In reality, the adoption of an outcome document as a criterion for qualifying the success or failure of a review conference is neither wise nor really useful for two main reasons: a consensus can be reached on a document that is poor in substance; a consensus outcome document is not legally binding. Conversely, the history of the NPT provides a number of conferences whose outcome was not a consensus document but which can be considered true collective successes in terms of consolidating the non-proliferation norm. For instance, the 1990 conference, which was particularly dense, generated a new approach to IAEA safeguards and took the issue of nuclear safety to heart for the first time in the examination of peaceful uses of energyRobert Einhorn, The 2020 NPT Review Conference: Prepare for Plan B, UNIDIR, 2020, 28 p.. This was also obviously the case of the 1995 Conference, which, without producing a substantive final document by consensus, was the opportunity to adopt four major decisions to strengthen the NPT, including the decision to extend the implementation of the Treaty for an unlimited period of time. Ultimately, the time spent by a conference seeking impossible consensus or skilful formulas to stifle disagreements by sparing diplomatic positions can be seen as time wasted in considering issues that could undermine the Treaty in real terms.

Then, the second half of the year 2020 is an opportunity to look in detail at the achievements of the NPT over the past fifty years. The anniversary of the Treaty's entry into force is not just an occasion for official celebrations, which will in any case be suspended this spring and summer. It is also and above all an opportunity to revisit the history of the NPT with this main question in mind: what were the real factors that have strengthened and weakened the Treaty over the past fifty years? Addressing this question in historical terms would make it possible to question many certainties, most of which are often peddled in good faith. For example, to say that the 2010 Review Conference was a success because a final document was adopted with an action plan on the three pillars of the Treaty makes diplomatic and political sense, but is not accurate in strategic and security terms: the Additional Protocol to the IAEA safeguards agreements was not promoted as the universal verification standard for the Treaty; the strengthening of the withdrawal clause of the Treaty (Article 10) did not give rise to any concrete initiative; the States Parties could not agree on a moratorium on the production of fissile material pending the launch of negotiations on a Cut-off Treaty; Action 58 merely “continue to discuss” the development of multilateral approaches to the fuel cycle, as the Western states' plan to promote “global governance” of nuclear energy under the auspices of article 4 of the Treaty was hampered by the fears of the NAM states that the mechanism was intended to restrict access to civil nuclear energy for developing non-nuclear-weapon states; and finally, the Conference was unable to adopt any of the proposals put forward to strengthen the institutional review process of the Treaty. Ultimately, the lack of substance in the action plan revealed the structural fragility of the NPT since the turn of the century, masked by President Obama's Prague speech of April 2009, the signing of the New START Treaty in April 2010, and the diplomatic success of the 2010 meeting. Hammered out as a motto, the so-called “success” of 2010 did not make it possible either to correctly anticipate the failure of the 2015 conference or to place the two events in a coherent historical continuity.

Whether the next NPT conference results in an expected failure or an unexpected success, its postponement represents an opportunity. It is not a question of exaggerating its scope, however: it is a timely opportunity to start refocusing the instrument on its priorities. In short, four issues will now be critical for the continuation of the process:

- Technological issues are to be understood as factors that strengthen or weaken the NPT;

- The legal-political issues will increasingly determine the quality of states' compliance with their commitments under Articles 4, 6 and 10 of the Treaty;

- Issues related to the dynamism of the review process itself have become unavoidable;

- Lastly, the field of regional matters must be addressed as an issue in its own right in the review of the Treaty, be it proliferation crises or the Middle East question.

The detailed formulation of these issues, their thorough analysis and the formalization of operating recommendations can be achieved by the end of 2020.

Nuclear Planet: the NPT and Covid-19

Note de la FRS n°46/2020

Benjamin Hautecouverture,

June 2, 2020