The port of Alexandroupolis: a strategic and geopolitical assessment

Introduction

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the small Greek Aegean port of Alexandroupolis, located close to the Bulgarian and Turkish borders, has emerged as a logistic and military hub serving the Western containment and deterrence strategy towards Russia. In this respect, it has been characterized as “vital” by various officials, analysts and media. Yet, its strategic significance had already started growing well before 24 February 2022.

The present study aims at shedding light on the roots of Alexandroupolis’ evolution into a strategic hub, at examining the multifaceted forms of the port’s strategic role, and at discussing its future perspectives and the challenges it faces and may further face in the future.

General background of Alexandroupolis

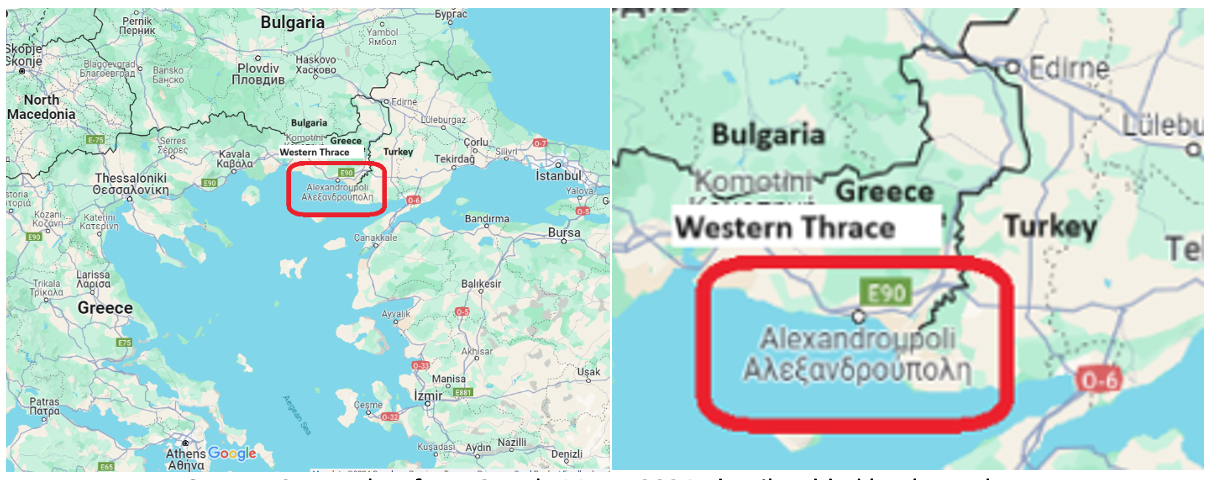

Alexandroupolis is a Greek port located on the Aegean Sea, at the north-eastern tip of Greece. With a population of 70,000, it is a rather modest and remote provincial city.

The location of Alexandroupolis

Source: Screenshot from Google Maps, 2024; details added by the author

The port was founded in 1872 – three years after the Suez Canal became operational – as a hub connecting by rail the Danube hinterland directly with the Mediterranean, thus bypassing the Bosporus and the Dardanelles (hereinafter: “the Straits”). As such, it progressively caught the attention of the great powersBy 1912, eight countries had a consular office in the city: Greece (the city was still on Ottoman territory), France, the United Kingdom, Persia, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy.. Τhis was especially the case for Russia, who briefly controlled it in 1878 and designed its urban planning on the model of Odessa. It was also continuously coveted by Bulgaria – Russia’s bridgehead in the Balkans – as a direct exit to the sea. Consequently, the city changed hands many times during the turbulent 1878-1920 period.

Finally awarded to Greece in 1920, Alexandroupolis saw its population increase due to the influx of Greek refugees from the Balkans and Asia Minor, but its role as a commercial knot was deeply altered. Following Europe’s political and territorial reorganisation after World War I, the city was no longer at the crossroads of flourishing trade routes, but at the very edge of a nation-state exhausted by consecutive wars. Later, the Cold War intensified this dead-end effect, as the city was only 40 km from the Iron Curtain, while, from the 1970s onwards, its development was further hampered by souring Greek-Turkish relations.

However, Europe’s post-Cold War political, geopolitical and economic reorganisation emerged as an outstanding opportunity for Greece to open up its northern regions and put them on major regional trade axes so as to improve its overall geopolitical standing. In the 1990s and 2000s, the building of the Via Egnatia motorway that virtually connects Turkey to Italy through the ports of Alexandroupolis, Kavala, Thessaloniki, and Igoumenitsa enhanced northern Greece’s east-west connectivity. However, as far as Alexandroupolis is concerned – and as boldly asserted by the port authoritiesInterview with the port authorities, fall 2023. –, it is first and foremost by investing on a north-south direction that it can truly hope to develop. Indeed, given its location, Alexandroupolis is an appropriate choice as an alternative (in the sense of complementarity) to the Straits, whose strategic value gives Turkey significant leverage over regional developments.

The first illustration of this north-south dynamic was the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline. First envisioned in 1994, its trilateral implementation agreement (Russia-Bulgaria-Greece) was signed in 2007. According to the plan, Caspian crude oil would be carried by tankers from Novorossiysk, Russia, to the Bulgarian port of Burgas, and then by land pipeline to Alexandroupolis, before being delivered to the world market by sea, thus bypassing the Straits. However, despite initial enthusiasm, Bulgaria withdrew from the project at the turn of the 2010s. Although various non-geopolitical reasons were evoked, this cancellation is also to be apprehended through the wider prism of the progressive resumption of the Russian-Western rivalry in the Balkans.

Today, this north-south dynamic is even more relevant, as the use of the Straits poses increasing challenges. The most important is congestion: six to ten days are needed to reach Romania from the Aegean – with random disruptions adding unpredictabilitySee, for instance: “Forest fire shuts Turkey’s Dardanelles Strait for maritime traffic”, Reuters, 22 August 2023; “Wildfire Halts Partly Vessel Traffic In Dardanelles Strait”, The Shipping Telegraph, 20 June 2024; Burak Akay, “Southward traffic resumes in Türkiye's Canakkale Strait after ship malfunction causes brief halt”, Anadolu Agency, 22 June 2024. – whereas, according to the port authorities, the Alexandroupolis-Constanţa (port to port) rail journey takes henceforth 2.5 days, without prioritising the train. Besides, the cost of the transit via the Straits is escalatingTransit fees increased more than sixfold between 2022 and 2024 (Vadim Kolisnichenko, “Turkey raises the cost of passage of ships through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles”, GMK Center, 14 June 2024)., while the future of Black Sea shipping remains uncertain due to the situation in Ukraine. Therefore, the improvement of transport velocity between Alexandroupolis and its northern hinterland gains relevance as a way to reduce overreliance on the Straits.

The gradual development of the strategic relevance of Alexandroupolis before the war in Ukraine

A dynamic geopolitical situation

Against the backdrop of Russia’s interventions in Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014) and Syria (2015), the United States started to engage more firmly in containment and deterrence in the area extending from the Baltic to the Mediterranean and the Black Seas. In this scheme, the posture of Greece and Turkey, who “lock” the passage between Balkan/Eastern/Pontic Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, appeared critical.

While Greece confirmed its bond with the West despite the dilemmas it faced during its financial crisis, Turkey made a very clear U-turn, moving further away from the West and closer to Russia. In short, while remaining important as a Black Sea, Caucasus and Middle East power, Turkey was becoming too demanding and unpredictable for the United States, whereas Greece appeared as a more loyal and suitable partner at a time of hardening competition with Russia on the European strategic theatre. It is within the context of this creeping rivalry between Moscow and Washington that Alexandroupolis, as the southern maritime outlet of the north-south containment axis allowing to lessen reliance on the Straits (and on Turkey), started to progressively acquire a strategic value for actors other than Greece.

Alexandroupolis and Russia

Obviously, this regional configuration in the making since the late 2000s was well decrypted in Moscow. From the 2010s onwards, Russia sought to secure its access to the Balkans and hinder American presence where possible. Alexandroupolis fitted neatly into this picture. The Russians endeavoured to gain footing in the city through a multi-dimensional soft power strategy involving the local administrative, economic, cultural, educational and spiritual authorities. A symbolic peak was eventually reached in 2016, when the Evros (Alexandroupolis’ regional unit) Chamber of Commerce and the Alexandroupolis City Hall signed cooperation agreements with the authorities of the Crimean city of SimferopolIlya Izotov, “Greek city of Alexandroupolis will trade with Simferopol”, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 19 February 2016 (in Russian).. Although this was not the first case of a post-annexation cooperation attempt between a Greek and a Crimean cityIlya Izotov, “Feodosia and the Greek city of Aspropyrgos signed a memorandum”, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 19 February 2015 (in Russian). – and not even a Greek peculiarityIlya Izotov, “Kerch signed a memorandum with the Italian province of Reggio Calabria”, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 30 November 2014 (in Russian). –, it was, however, not in line with the Greek and EU official position, namely that the annexation of Crimea was illegal.

This rapprochement was part of a more general calculation. The local authorities hoped for economic benefits for their city in a context of severe financial crisis and amid popular distrust towards the national and European political elite. For its part, Russia, which already benefited from Turkey’s ambivalence, hoped to cultivate the “strategic porosity” of the Greek part of a geographical area whose strategic order determines the terms of passage between Balkan/Eastern/Pontic Europe and the Eastern/Central Mediterranean. Τhe Ukrainian conflict has boldly confirmed the importance of this area.

However, against the backdrop of Russia’s increasing influence in the city between 2011 and 2016, the conditions for a counter-phenomenon gradually emerged. First, with the annexation of Crimea in 2014, which instigated a progressive increase in the US military presence in Europe and a greater awareness in the EU regarding the need to diversify energy providers“European Energy Security Strategy”, European Commission, 28 May 2014. – although with obviously poor results. Then, with the 2015 financial bailout program, which confirmed Greece’s bond to the EU and commitment to reforms, which go hand in hand with the gradual recovery of its strategic status; this paved the way for its greater strategic alignment with the United States, which, in turn, incited its gradual distancing from Russia. Finally, with the development of the American presence in the city from 2016 onwards, which eventually supplanted Russia and progressively vested Alexandroupolis with strategic importance for the West.

Alexandroupolis and the Greek-American strategic synergy

In 2016, the US ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt – a vocal supporter of the Maidan movement (2014) – was transferred to Athens, before returning to the United States in 2022 as Assistant Secretary of State for Energy Resources. It was during his mandate in Greece that Alexandroupolis evolved into the maritime pivot of the vertical energy and military corridor aimed at deterring and containing Russia along the EU’s eastern flank; to take his own words, “[t]his was a region which, when I arrived in Greece in 2016, seemed somewhat forgotten. This is no longer the case”“US strategically committed to northern Greece, Pyatt tells ANA from Alexandroupolis”, Athens-Macedonia News Agency (AMNA), 7 May 2021.. At the same time, the abortive coup d’Etat in Turkey in July 2016 intensified the Russian-Turkish rapprochement and Ankara-Washington distancing, thus boosting the Greek-American strategic synergy and the strategic upgrade of Alexandroupolis.

Since 2019, the website of the US embassy in Athens has featured a fact sheet on the port, describing it as “well positioned to support exercises in the region due to its existing infrastructure and strategic location” and “of significant importance for the flow of personnel and equipment”FACT SHEET: Alexandroupolis Port, U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Greece, 11 September 2019.. Accordingly, it was the US military that bore the cost for the removal of a dredger that had sunk in the port and was preventing its optimal use. Besides, American analysts that take a hard line against Turkey (and, a fortiori, against Russia) started to stress the importance of the port as the pivot of the American military presence in the regionSee, for example, “U.S. & Greece: Cementing a Closer Strategic Partnership”, Jewish Institute for National Security of America, January 2020; Eric Edelman, Charles Wald, “Greece Is at the Nexus of America’s Geopolitical Crossroads”, The National Interest, 7 February 2020; “At the Center of the Crossroads: A New U.S. Strategy for the East Med”, Jewish Institute for National Security of America, November 2021.. From 2020 onwards, Alexandroupolis became a hub for the American forces joining EU/NATO’s eastern flank, including in the context of large NATO drills“Ambassador Pyatt’s Remarks at DEFENDER-Europe 21 DV Day”, U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Greece, 7 May 2021; “Ambassador Pyatt’s Remarks at Atlantic Resolve Distinguished Visitors Day”, U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Greece, 3 December 2021; Tevfik Durul, Derya Gulnaz Ozcan, “Largest-ever US military shipment set to arrive in Greece in November”, Anadolu Agency, 18 October 2021; Lt.Cmdr. Kartik Parmar, Cmdr. Cameron Rountree, “Military sealift command supports theater cooperation in Europe again”, US Navy’s Sea Lift Military Command, 11 January 2022..

Greece, for its part, welcomed the US-fuelled strategic upgrade of Alexandroupolis. The latter has evolved into a paradigm of the Greece-US strategic synergy, especially as embodied in the Mutual Defence Cooperation Agreement, whose 2021 extension and amendment namely mentions Alexandroupolis“Protocol Between the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and GREECE Amending Agreement of July 8, 1990, as Extended and Amended”, art. II, U.S. Department of State, 14 October 2021.. On the one hand, the United States uses Alexandroupolis to further deter and contain Russia while delivering only indirectly and at low cost the message to Ankara that, despite its importance as a NATO member and regional power, reliable alternatives do exist. On the other hand, by upgrading Alexandroupolis, Greece also seeks to deter its turbulent eastern neighbour, as the more US, NATO and EU assets concentrate in this region, the less Greece is exposed to Turkey’s strategic leverage. And it is no coincidence that Alexandroupolis’ development as a strategic hub annoyed concurrently Moscow and Ankara.

The Turkish pro-government press has regularly attacked in a deliberately exaggerated manner the growing military importance of the port, portraying it as a direct security threat to Turkey and even to its president personallyFor example: Bulent Orakoglu, “Why is the US amassing tanks in Greece under the guise of war games? Is Turkey the target?”, Yeni Safak, 28 September 2021; Ibrahim Karagul, “A horrific deal was made to topple Erdoğan! US troops in Alexandroupoli are set to cross the border. An unprecedented betrayal is afoot!”, Yeni Safak, 13 December 2021; Panagiotis Savvidis, “The presence of American helicopters in Alexandroupolis is a challenge: Turkish media”, Greek City Times, 30 January 2021; Panagiotis Savvidis, “‘30 American helicopters at Alexandroupolis is a bad development’: Retired Turkish brigadier general”, Greek City Times, 2 February 2021.. Turkish officials, including the head of State, have also expressed discontentFor example: Manolis Kostidis, “Rafales, Alexandroupoli base irk Erdogan”, Kathimerini, 2 November 2021; Jim Zanotti, Clayton Thomas, “Turkey (Türkiye): Background and U.S. Relations”, Congressional Research Service Report R41368, 9 January 2023, pp. 37-38.. In addition, in 2022 Turkey violated the Greek airspace near Alexandroupolis for the first timeStatement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding the unprecedented violation of Greece’s national sovereignty by Turkish fighter aircraft near Alexandroupolis, Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 20 May 2022.. Airspace violations are a recurrent Turkish practice over Greek islands and the Aegean SeaJoint Communication to the European Council. State of play of EU-Türkiye political, economic and trade relations, European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 29 November 2023, p. 2. and are part of a strategic contestation logic. However, Turkey had never proceeded to such a violation in the Alexandroupolis region in the past; thus the violation revealed Ankara’s deep irritation caused by the city’s increasing strategic footprint.

The upgrade of Alexandroupolis also raised eyebrows in Moscow“Russia concerned by US military buildup in Eastern Mediterranean — foreign ministry”, TASS, 2 October 2020; “Moscow dismay over Alexandroupoli”, Kathimerini, 11 December 2021; “Lavrov: Russia is ‘annoyed’ for the US base in Alexandroupolis”, Protothema, 14 January 2022.. Retrospectively, it appears that the way in which Russia tried to gain footing in the city in the 2010s was rather to prevent the development of American influence there than to use the port for its own military purposes. In fact, in terms of military projection, the port is far more important for the United States than it is for Russia, whose navy is more interested in docking southwards in order to project power in the maritime area stretching from Libya to Syria. Thus, once the US chose Alexandroupolis as a maritime pivot to Balkan/Eastern/Pontic Europe, Moscow had nothing significant to oppose.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 has accelerated and amplified these dynamics that have developed since 2014, and has increased the attention of foreign officialsFor example: C. Todd Lopez, “Strategic Port Access Aids Support to Ukraine, Austin Tells Greek Defense Minister”, U.S. Department of Defense, 18 July 2022; “Visite de l’Ambassadeur à Alexandroúpolis (28-29/11)”, French Embassy in Greece, 29 November 2022; “Ambassadors of the EU visited the Alexandroupolis Port Authority”, Ports Europe, 22 January 2023; “U.S. diplomats visits Alexandroupolis Port Authority”, Ports Europe, 7 February 2023; Joint visit by Deputy Defence Minister Nikolaos Hardalias and the US Assistant Secretary of Defence for International Security Affairs Dr. Celeste Wallander to Alexandroupoli and Larissa, Greek Ministry of National Defence, 20 February 2023; “Port of Alexandroupolis welcomes stream of ambassadors”, Ports Europe, 7 June 2023; “Escale de la frégate FREMM Languedoc à Alexandroúpolis (10 avril 2023)”, French Embassy in Greece, 10 April 2023., mediaFor example: “A sleepy Greek port has become vital to the war in Ukraine”, The Economist, 21 July 2022; Niki Kitsantonis, Anatoly Kurmanaev, “Sleepy Greek Port Becomes U.S. Arms Hub, as Ukraine War Reshapes Region”, The New York Times, 18 August 2022; Peter Voegeli, “Ein kleiner griechischer Hafen wird zum Zentrum der Geopolitik”, SRF, 11 August 2023. and analystsFor example: Jake Sotiriadis, John Sitilides, “U.S. and Greece Take Strategic Partnership to New Heights”, The National Interest, 16 May 2022; Alan Makovsky, “A. Makovsky Testifies Before the House Foreign Affairs Committee”, Jewish Institute for National Security of America, 19 March 2022; Jonathan Ruhe, Ari Cicurel, “Without Alexandroupolis, Transatlantic Security Is Dead in the Water”, Jewish Institute for National Security of America, 29 August 2022. for Alexandroupolis.

Alexandroupolis since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine: towards the crystallization of an Aegean-Baltic axis?

The strategic and military dimension

Although this would require a tremendous military effort on the part of Russia, a situation resulting in denying maritime access to Ukraine cannot be ruled out axiomatically. Besides, the alignment of Turkey – the other sizeable Black Sea naval power – with Western interests is less than certain, as Ankara traditionally seeks to maintain its strategic autonomy and a dynamic of synergy with Moscow in the areaOn the Turkish posture in the Black Sea, see, for instance, Daria Isachenko, “Turkey in the Black Sea Region. Ankara’s Reactions to the War in Ukraine against the Background of Regional Dynamics and Global Confrontation”, SWP Research Paper, n° 12, October 2023.. Against the unpredictability of the Black Sea strategic order, tried-and-tested alternative routes linking Central, Eastern, Pontic and Baltic Europe to the Aegean via Alexandroupolis do make sense for the West.

In purely military terms, Alexandroupolis revealed its full potential in 2022. The Russian invasion of Ukraine exponentially increased the need for American projection along NATO’s eastern flank, especially to Romania, who shares borders with both Ukraine and Moldova. In this context, Alexandroupolis proved to be crucial. According to the port authorities, between the start of the war in Ukraine and the summer of 2023, no less than 60 percent of US military forces joining or leaving Europe transited through the port. This impressive number, be it exact or approximative – competent US military authorities that were contacted did not confirm or refute it –, amply justifies the depiction of Alexandroupolis as a strategic hub. What is more, Greek media reported that in summer 2022 the port received the largest ever batch of equipment in the US army’s history to transit through a single port, while, in March 2024, for the first time an entire armoured brigade moved through it, which is a demanding operationSgt. 1st Class Terysa King, “Port of Alexandroupolis makes sustainment history with heavy brigade movement”, US Army, 17 March 2024.. The critical role of Alexandroupolis was reasserted in 2024 by US officials“US Ambassador Tsunis: Greece secures NATO readiness via Alexandroupolis”, Association of the Balkan News Agencies Southeast Europe, 17 March 2024., including in the 2024 Joint Statement on the US-Greece Strategic Dialogue, in which it is described as “a vital logistics, energy, and supplies chain hub”Joint Statement on the U.S.-Greece Strategic Dialogue, US Department of State, 9 February 2024..

This is particularly relevant as Turkey, although a NATO member, is not eager to become a hub for Western forces in the context of the war in Ukraine. Firstly, because this implies imperilling the Turkish-Russian relationship, which Turkey cannot afford in the current state of affairs. Indeed, this would compromise a core feature of its foreign policy: its balancing act and transactional approach. Secondly, because Turkey decided to suspend the transit of warships through the Straits. This prerogative, which derives from the 1936 Montreux Convention, is an undeniable asset enabling Turkey to act as a strategic regulator of the Black Sea, which is a traditional area of competition between the West and Russia. Although the decision to close the Straits was praised by the United States, the extent of Turkey’s discretionary powers under the Montreux Convention can also produce controversial results for the West, such as the blocking of the minehunters donated to Ukraine by the Royal NavyStatement regarding disinformation about UK mine hunting ships, Turkish Presidency’s Directorate of Communication, 2 January 2024.. Given the defensive character of such ships, Turkey’s decision was eventually criticized as excessiveGabriel Gavin, “Turkey must stop blocking Ukraine minehunters, ex-NATO supreme commander warns”, Politico, 5 January 2024., implying that it proceeded from an unfriendly political calculus towards the West. But this Turkish privilege has also had a perverse effect for Ankara. It featured the relevance of Alexandroupolis as the pivot of a land-based military corridor between the Aegean and the Black Sea allowing Western countries to bypass the Straits, thus depreciating a major Turkish strategic asset. At the same time, Russia can no longer send its warships through the Straits.

Furthermore, the port authorities have emphasized the security situation in the Baltic Sea, portraying the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad as a constant threat which, if tension was to further escalate, could challenge the unimpeded access of Western countries to the Baltic Sea. And it is a fact that the security balance in the Baltic is increasingly under pressure, including for Russia and Belarus, following Sweden’s and Finland’s accession to NATO“Meeting with Governor of Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast Anton Alikhanov”, <Belarusian Presidency, 5 June 2023; “Defense ministry looking at extending Estonia's maritime control zone”, Eesti Rahvusringhääling (ERR), 6 December 2023; Natalya Markushina, “The Changing Security Configuration and Balance of Power in the Baltic Region: Implications for Russia”, Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), 5 October 2023; Konstantin Khudoley, “Baltic Sea Region: New Realities and New Problems”, RIAC, 8 December 2023; “Belarus conducts military drills near Ukraine, EU border”, Deutsche Welle, 2 April 2024.. Against this backdrop, the port authorities have presented Alexandroupolis as a completely safe harbour for Western maritime military flows, as it is both close to the forces’ concentration zone along EU/NATO’s eastern flank and much less exposed to Russia’s military power as compared to the Baltic.

In this context, other NATO members have started to use Alexandroupolis for military purposes, notably the United Kingdom (UK), Italy and France. In the case of France, this has created further discontent in Turkey“Greece move to open key port to French Army likely to anger Türkiye”, Daily Sabah, 28 July 2023; Laurent Lagneau, “La Turquie prend ombrage de l’intérêt des forces françaises pour le port grec d'Alexandroupoli”, Opex360, 3 August 2023., which is already upset with the French-Greek strategic synergy.

The energy dimension

The war in Ukraine has pushed to the top of the Western agenda the objective to reduce energy overreliance on Moscow. The liquified natural gas (LNG) has a prominent role in this process. Accordingly, the EU energy flows are switching from a mainly vertical and rigid logic based on land or subsea gas pipelines connected to Russia to a “network” logic, which includes maritime flows and the multiplication of LNG units along European coasts. The aim is to spread the risks in terms of infrastructural safety, as well as geopolitically, as it facilitates the diversification of suppliers and routesSee « La décontinentalisation des flux énergétiques en Europe », Brèves marines, CESM, n° 274, 25 April 2023; Aris Marghélis, “Challenges of the World Ocean in a Changing Strategic and Energy Security Context: The Case of the Eastern Mediterranean”, in Yannis Valinakis, Ioannis Stribis (eds.), EU Policies Towards its East Mediterranean Space: Energy and Security, Jean Monnet European Centre of Excellence, University of Athens, 2023, pp. 95-119, pp. 107-118.. In this respect, the investment in a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) in Alexandroupolis – the first in Greece – comes at just the right time. It is expected to be fully operational in 2024, with a capacity of 5.5 Bcm, approximately 70 percent of which is to be exported.

Redistribution of gas from the Alexandroupolis FSRU to Europe

Although it had received the status of Project of Common Interest by the European Commission as early as November 2014, this FSRU was inaugurated only in May 2022, in presence of the President of the European Council“Remarks by President Charles Michel at the inauguration of the floating liquefied natural gas terminal in Alexandroupolis”, European Council, 3 May 2022., of the leaders of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, and of the new US ambassador in Athens. The latter has consistently expressed support to the projectSee the a href="https://twitter.com/USAmbassadorGR/status/1487106848591429641">tweet from the US ambassador in Greece, 28 January 2022., rallying also Moldova and UkraineBill Kouras, “Tsunis: Key role of the FSRU at Alexandroupoli”, Greek City Times, 7 June 2023.. Besides, the Bulgarian company Bulgartransgaz has secured a 20-percent stake, as this unit is set to become key in the realization of the Vertical Corridor, the gas pipeline network connecting Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Strongly backed by WashingtonAdrian Stoica, “Extended Support for the Vertical Corridor”, Energy Industry Review, 18 March 2024., the Vertical Corridor is also expected to obtain EU funding“EU support sought for half of Vertical Corridor’s €450m budgeted cost”, Energy Press, 22 January 2024..

Therefore, via the energy vector, Alexandroupolis is expanding its strategic role, as even Moldova and Ukraine are now target gas recipients from its facilitiesMadalin Necsutu, “Moldova and Ukraine to Receive Gas from Greece”, Balkan Insight, 4 May 2022; Razvan Timpescu, “Moldova imports US-sourced LNG from Greece”, SeeNews, 3 April 2024. with a view to facilitate their integration into the Western energy, economic and infrastructural system. In this respect, the fact that the Greek operator DEPA won the tender to supply gas to the Moldovan national company Energocom in 2023See “Moldova signs contract for gas supplies from Greece, depriving Gazprom of another market”, The New Voice of Ukraine, 7 April 2023. and that the Greek Public Power Corporation actively invests in the Romanian energy marketIgor Todorović, “PPC buys Enel Group’s operations in Romania”, Balkan Green Energy News, 9 March 2023; Chryssa Liaggou, “Why PPC’s Romanian purchase is important”, Kathimerini, 11 March 2023; Alexandru Cristea, “Greece’s PPC buys 84 MW Romanian wind farm from Lukoil”, SeeNews, 27 March 2024. demonstrates Athens’ interest in this region.

This FSRU project is coupled with two other energy projects. Firstly, a natural gas-fired electricity generation plant designed to meet local and regional consumption needs in order to increase Greece’s role in the energy security of Southeast Europe. It is expected to be operational in 2026. Secondly, a pipeline linking Alexandroupolis to Burgas, to enable Bulgaria to reduce its high dependence on Russian oil“Radev: Construction of Alexandroupolis - Burgas Oil Pipeline Will Provide Real Diversification and Alternative Oil Supplies for Largest Refinery in the Balkans and the Black Sea Region”, Bulgarian presidency, 16 February 2023.. It is the same pipeline that was planned in the 1990s, but in the opposite direction: it is now designed to provide Bulgaria with oil and gas arriving by sea through Alexandroupolis. Undoubtedly, this is the epitome of the correlation between geopolitical upheaval and the reorganisation of energy routes.

All in all, this enterprising mindset in the energy field is part of Greece’s efforts to optimise its position as the first continental EU country located on the maritime route connecting the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region and the Indo-Pacific to Europe, while it evidences Alexandroupolis’ key position in this scheme. That said, nothing should be taken for granted. This reorganization of energy routes that benefits Greece is an ongoing process. Therefore, it is vulnerable to vagaries and counter-strategies. It is true that the EU has decreased its gas imports from Russia from 175-180 bcm in 2018-2019 to 63,8 in 2022 and 28,3 in 2023“Russia's pipeline gas exports to Europe jump in June from last year”, Reuters, 2 July 2024., marking an all-post-Soviet time low. However, in the first half of 2024, imports of Russian piped natural gas (PNG) increased by 24 percent on a year-to-year basis“Monthly Gas Market Report”, Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), July 2024, p. 24.. In the same period, the import of LNG has dropped by 20 percent, including due to the increase in PNG importsIbid., p. 28.. Prominent Greek analysts have claimed that Russia started to artificially decrease the price of PNG destined to the EU in late 2023 precisely in order to cancel the dynamic of the Vertical Corridor before it acquires economic viabilityFor instance: Michalis Mathioulakis, “Russia cancels the energy plans of EU – Greece”, Energygame, 13 July 2024 (in Greek).. At the same time, Ukraine, via which half of the Russian PNG destined to the EU still transits, will probably not extend its contract with Gazprom, which expires at the end of 2024. It remains to be seen whether this will boost LNG imports, including through Greece, or if Turkstream, via which the other half of Russian PNG transits, will see a further increase in deliveries (also taking into account the face that PNG remains cheaper than LNG).

The transport infrastructure dimension

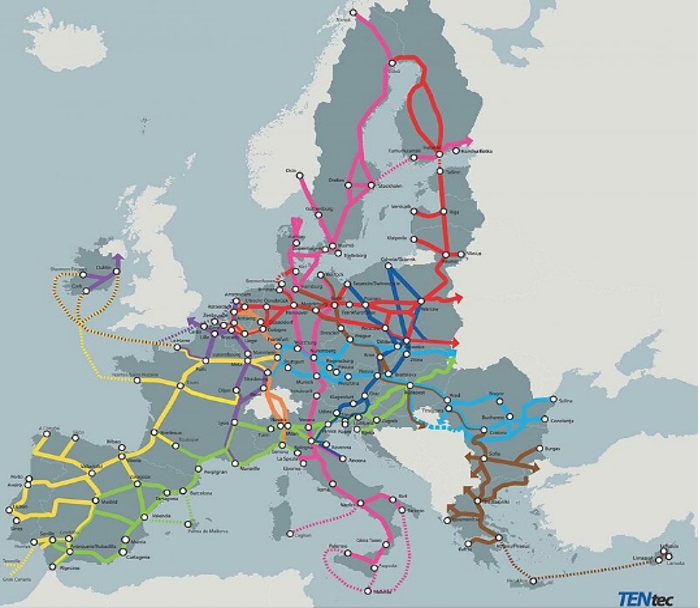

The war in Ukraine has crystallised the East-West rupture along EU/NATO’s eastern flank, generating the need to strengthen the North-South axis linking the Baltic to the Aegean. This implies addressing a recurring shortcoming of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), which has remained essentially structured on an East-West logic.

The TEN-T

Source: Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Indeed, cross-border connections between the EU and Russia/Belarus become increasingly random. Among other, this severely affects the Baltic states and their ports, given that, as former Soviet republics, they remain better connected to Russia and Belarus, while the exclave of Kaliningrad on their south-western flank further complicates their connection to the EU. Accordingly, this East-West rupture in the centre of geographical Europe raises new needs in terms of logistic solidarity and connectivity. Russia and Belarus are increasingly looking NorthAtle Staalesen, “Belarus sends prime minister and military leaders to Murmansk”, The Barents Observer, 1 June 2023; “Belarus says Russian ports now used for transshipment”, Ports Europe, 25 July 2023; Atle Staalesen, “Lukashenko wants access to Russian Arctic seaports”, The Barents Observer, 30 January 2024; “Belarus, Russia in talks on cargo transshipment through Russia’s Arkhangelsk port”, BELTA, 22 April 2024., SouthMaziar Motamedi, “Iran and Belarus sign cooperation roadmap in Lukashenko visit”, Al Jazeera, 13 May 2023; Ivan Nechepurenko, “From Moscow to Mumbai: Russia Pivots South for Trade”, New York Times, 13 March 2024. and East“Lukashenko calls for consolidating Belarus’, Russia’s, China’s industrial potentials”, TASS, 27 February 2023; “Belarusian leader visits China amid Ukraine tensions”, Associated Press, 28 February 2023; “Lukashenko: China and Belarus share the same vision of world order”, Republic of Belarus, 17 August 2023; “China, Belarus seek closer military ties”, Deutsche Welle, 17 August 2023; “Arkhangelsk port as China’s cargo transport hub”, Ports Europe, 9 June 2024; “Belarus becomes full-fledged SCO member”, Interfax, 6 July 2024; Isaac Yee, Ivana Kottasova and Simone McCarthy, “China and Belarus conduct joint military exercises right next to NATO and EU’s border”, CNN World, 9 July 2024. for solutions. On their side, the EUDesislava Toncheva, “EC Encourages Romania and Bulgaria to Submit Fast Danube 2 Project”, BTA, 18 October 2023; “European Commission: Rail Baltica must be ready by 2030”, ERR, 8 February 2024; Justina Budginaite-Froehly, “Baltic Defense: Getting New Rail Links Back on Track”, Center for European Policy Analysis, 16 July 2024., as well as the US, the UK and even Switzerland and Japan display commitment to strengthening North-South connectivity, including by setting up the Baltic-Black-Aegean Seas (BBA) corridor“International Transport Forum Joint Statement”, Lithuanian Ministry of Transport and Communication, 10 April 2024..

The core question that underpins this infrastructural transformation project is whether the security emergency stemming from the situation in Ukraine has overtaken the primarily economic considerations that are supposed to guide infrastructure development. Apparently yes, in two ways.

First, in the short term, by fostering the infrastructural development for dual military-civil use due to the strategic situation on the EU/NATO’s eastern flank“Military Mobility”, European External Action Service, November 2022; “Commission supports military mobility projects with €807 million”, European Commission, 24 January 2024.. This creates a form of economic profitability; however, its long-term viability is not guaranteed as it entirely depends on a given strategic situation that remains unpredictable.

Second, by the stimulation of long-term dynamics due to security and strategic urgency. Concretely, this means changing the whole infrastructural, economic and geopolitical rationale along the EU’s eastern flank. Accordingly, the strengthening of a North-South axis is determined by a geopolitical and strategic vision, not a purely economic one. In this context, funding is more readily available, as economic viability considerations are being complemented by strategic considerations in the funding process. For instance, despite years of Polish lobbying, it was not before December 2022 that components of the Via Carpatia – which connects Klaipeda (Lithuania) to Thessaloniki and Svilengrad (Bulgaria-Alexandroupolis junction) – were finally included in the TEN-T, which translates into substantial EU funding through the Connecting Europe Facility. However, the inescapable challenge will remain to vest these infrastructural projects with economic substance in order to make them viable on the long run and increase their resilience against geopolitical vagaries.

Alexandroupolis fits entirely in this picture. Indeed, it combines the two above-mentioned dimensions of the infrastructural reorganisation in the making along the Baltic-Aegean axis. Concretely, the key-infrastructure that will enable it to prosper beyond its role as military a hub is the railway. For instance, the first shipment to use a combined route (ship, rail) between Suez and Constanţa through Alexandroupolis was operated in 2020 at the port authorities’ initiative, a success they are particularly proud of. In addition, the Alexandroupolis-Ormenio/Svilengrad (Bulgarian border) rail link is being reactivated, with the construction of an electrified double line along the Greek-Turkish border. It is expected to be operational in 2028 at a cost of €1.078 billion and to improve Alexandroupolis’ connectivity and competitiveness. The fact that this funding comes from Greek public funds and not directly from the EU is interpreted by the port authorities as a strong sign of the Greek government’s commitment to the development of this rail line. And, indeed, Greece has diligently pushed for the development of an efficient rail connection with Bulgaria and Romania“Greece proposes launching trains to Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova to facilitate Ukrainian exports”, Interfax, 19 October 2023; “Bulgaria and Greece to build up military transport capacity”, Ports Europe, 22 January 2024; “Greece-Bulgaria-Romania trilateral meeting on establishing transport corridor”, Kathimerini, 14 March 2024..

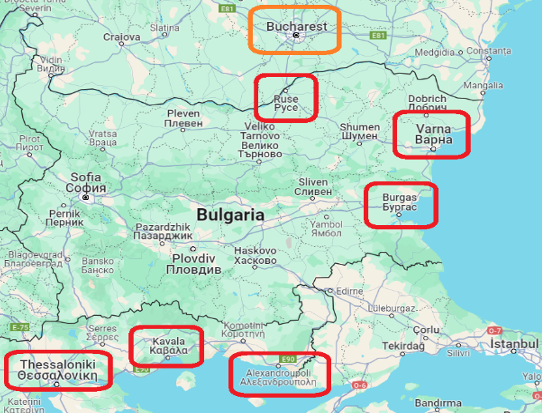

It is also worth evoking the “Sea2Sea” project between Bulgaria and GreeceMomchil Rusev, “Bulgarian Ambassador to Greece Stresses Importance of Sea2Sea Project as Alternative to Bosphorus, Dardanelles”, BTA, 10 September 2023.. It aims at connecting by rail the three northern Greek ports (Thessaloniki, Kavala, Alexandroupolis) to the three Bulgarian ports of Burgas, Varna and Ruse, the latter lying only 70 km from Bucharest.

The Greek and Bulgarian ports to be connected as part of the “Sea2Sea” project

Source: Screenshot for Google Maps, 2024; details added by the author

While the maturation of the Sea2Sea project was rather slow, the crystallisation of the geopolitical landscape along the EU/NATO’s eastern flank – reflected in the lasting distancing from Russia – seems to offer a more favourable context for its implementation. Accordingly, it was discussed at the two trilateral Greece-Bulgaria-Romania summits held in Varna in October 2023 and in Sofia in April 2024“Greece-Bulgaria-Romania trilateral meeting on establishing transport corridor”, AMNA, 14 March 2024., as well as between the Greek Transportation Minister and the TEN-T coordinator“Staikouras discusses new railway projects in Greece with European TEN-T coordinator Grosch”, AMNA, 18 October 2023..

Lastly, on the margins of the 2024 NATO summit in Washington, Greek, Bulgarian and Romanian defence ministers signed a Letter of Intent for the establishment of a Harmonized Military Mobility Corridor. It will connect Thessaloniki, Alexandroupolis, Varna and Constanţa (where the biggest NATO base in Europe is being built); it aims at facilitating the rapid movement of NATO troops in case of emergency. This supposes fluent connections and fewer transborder administrative obstacles. The first meeting to discuss the details of its implementation will be held in the fall of 2024 in Alexandroupolis“Bulgaria, Greece and Romania to set up military corridor in NATO’s Eastern flank”, Bulgarian National Radio, 11 July 2024..

These are concrete examples of how a challenging security and strategic context can initiate and boost the implementation of infrastructure projects.

Prospects and challenges

From the above, it becomes clear that the interlocking of multiple interests in Alexandroupolis and its region fulfils, at its level, several objectives. It enhances the Baltic-Aegean strategic, military, energy and economic corridor development. It serves the West’s attempt to integrate Ukraine and Moldova in its energy, economic and infrastructural system. It also satisfies part of Greece’s security needs in relation with Turkey and improves its positioning as an interface between Europe, the MENA region and the Indo-Pacific. Τhis creates significant opportunities for Greece to upgrade its geopolitical standing. Hence the suspension of the privatisation process of the port in 2022. This means the government intends to retain control on the port, whose development remains primarily a strategic issue that still needs to be managed at a high political level.

However, Alexandroupolis also faces outstanding challenges. On the one hand, the conflict in Ukraine – whose outcome remains uncertain – is critical for the future of the port, as attested by Greece’s repeated commitment to Ukraine’s security with regular reference to Alexandroupolis“Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ statements at a joint press conference with the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Odessa”, Greek Prime Minister, 6 March 2024.. On the other hand, much will depend also on Greece’s ability to expand and entrench its pivotal role on the arc extending from the Baltic to the Red Sea.

Alexandroupolis’ future as a military hub

A first challenge Alexandroupolis might be confronted with would be a substantial reduction of the flow of military personnel and equipment. This may happen if the Ukrainian conflict was to stall or even end, or if a US administration was to opt for disengagement. Yet, this is not necessarily the most likely scenario.

As pointed out by Michael RubinMichael Rubin is director of policy analysis at the Middle East Forum, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a former Pentagon official. The interview took place on 6 June 2024 by email. , Alexandroupolis remains a valuable spot close to an increasingly challenging Black Sea, considering that the United States has not many completely safe harbours in the Eastern Mediterranean. Therefore, while the situation in Ukraine is crucial, Alexandroupolis is also part of a wider geopolitical configuration that diversifies its opportunities. The port authorities, for their part, also seem confident, claiming that a reduction of Western military aid to Ukraine will not necessarily lead to a substantial US military drawdown from Europe. They point out that even if the number of American units stagnates, their rotation alone generates considerable logistic needs. Therefore, if Alexandroupolis continues catching US military flows at the current rate (60 percent, according to the port authorities), it will remain critical. Accordingly, Greece will be able to continue ripping the benefits associated with this positioning.

Alexandroupolis and the economic dimension of the Ukrainian conflict

The economic dimension of the Ukrainian conflict has two main aspects: the grain export and the reconstruction.

Concerning the grain, the agreement allowing it to leave Ukraine-controlled ports and move through the Straits was suspended in 2023. While Ukraine’s rather unexpected ability to disturb Russian naval presence in the Black Sea has so far allowed the resumption of maritime flows“Ukrainian grain exports rebound as ship arrivals near pre-war levels”, Loyd’s List, 26 April 2024., the overall security situation of the Black Sea remains highly challenging. On the long run, this requires the West to develop alternatives. In this context, the south-north land corridor that connects Alexandroupolis to Moldova and Ukraine may well be relevant for the West. Indeed, as Alexandroupolis’ connectivity with its northern hinterland is improving, Greece has steadily pushed for the transformation of the port into a hub for the Ukrainian grain on its way to the international marketSee Martin Fornusek, “Media: Greece, Bulgaria discuss transit of Ukrainian grain by rail”, The Kiyv Independent, 24 July 2023; “Greece offers to transport Ukrainian grain to its ports by rail”, Ukragroconsult, 23 October 2023..

In this scenario, the cereals would use a route Russia cannot interfere with, unlike the maritime route. The strikes on Ukraine’s river ports of Izmail and Reni that followed the suspension of the agreement – and which eventually ended up in costing Moscow’s participation to the Danube Commission“100th Jubilee Session of the Danube Commission”,Danube Commission, 14 December 2023. – suggest that an alternative to the Black Sea is realistic.

On their side, the port authorities of Alexandroupolis claimed to have foreseen the collapse of the grain agreement as early as in summer 2022 and exerted pressure on the EU Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE) to speed up the funding for the modernisation of regional road and rail infrastructure. They secured a €24 million budget under the European Commission’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, part of which will be allocated to the acquisition of high-speed grain loading infrastructure. According to the port authorities’ projections, Alexandroupolis could be able to handle part of the Ukrainian grain in one or two years. While several northern European ports are generally better equipped and already trade Ukrainian grain, Alexandroupolis offers the shortest land route between Ukraine and the Mediterranean Sea, and the shortest sea route between Europe, the MENA region and Asian countries, which are among the main recipients of Ukrainian grain. Therefore, once provided with the necessary infrastructure, Alexandroupolis can hope to become competitive in this field.

As far as Ukraine’s reconstruction is concerned, any projection is still premature since much will depend on the territorial reality that will emerge from the conflict, whenever it ends. However, a future reconstruction will generate colossal material needs given the task at hand. In this respect, Greece strives to create the conditions for its involvement in the reconstruction process“Conference in Athens discusses plans for Ukraine reconstruction”, Euronews, 16 February 2024., especially by using Alexandroupolis as a knot“Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ statements at a joint press conference with the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Odessa”, >The Prime Minister of Greece, 6 March 2024.. Besides, along with grain exports, Ukraine’s reconstruction might well favour Greek shipowners, who control 25 percent of the bulk carriers’ world tonnage (80 percent at EU level)“2022-2023 annual report of the Union of Greek Shipowners”, Union of Greek Shipowners, 2023, p. 11, p. 15. but express discontent with shipping being increasingly exposed to geopolitical contingencies and subject to unilateral restrictions perceived as unfairIlias Bellos, “Shipowners protest over ‘unfair’ criticism”, Kathimerini, 12 June 2024..

Conclusion: the way forward

While Alexandroupolis has managed to emerge as a strategic hub under specific geopolitical circumstances, the highly volatile geopolitical context may also challenge this dynamic. Accordingly, its future development relies on several conditions.

Firstly, the disconnection of the United States’ interest for Alexandroupolis from a potential reset of US-Turkey relations, as Turkey keeps being annoyed by the military use of the port and might well raise the issue in future negotiations. A certain decrease of the buzz on Alexandroupolis and the relativisation of its importance before the Turkish audience by US officials“Türkiye-US partnership stronger than ever: Envoy”, Hürriyet Daily News, 12 June 2024. can be associated to the current thaw in US- (and Greece-) Turkey relations. Yet, there are few doubts in Washington that Ankara will remain a complicated and eventually undependable partner over the long run. Along with guaranteeing an elementary leverage on Turkish affairs, this requires for the United States to continue diversifying optionsAs also suggested by the latest developments in US-Cyprus strategic relations (see, for instance, Menelaos Hadjicostis, “US, Cyprus embark on strategic dialogue that officials say demonstrates closest-ever ties”, Associated Press, 17 June 2024). . As Michael Rubin corroborates, the United States will keep on lessening reliance on Turkey regardless of any improvement in bilateral relations, since Ankara’s long-term commitment to the West is not guaranteed. In this context, he asserts, alternatives such as Alexandroupolis are not expected to be depreciated and the importance of the port meets bipartisan and trans-administration consensus in the US.

Secondly, Greece’s aptitude to build, operate and protect an efficient transport and energy infrastructure. 2023 was particularly tough for Greece’s infrastructure, especially for its railway network, part of which was paralysed for months due to unprecedently severe natural and man-made disasters. In addition, the whole – densely forested – region of Alexandroupolis was devastated by the largest wildfire ever recorded in the EU amid strong suspicions of arson. With transport and energy infrastructure becoming increasingly strategic and, accordingly, vulnerable to deliberate damage, Greece has to ensure the security and resilience of its infrastructure so as to cope with the responsibilities it is taking on. The increasing involvement of the intelligence and armed forces in dealing with such disasters, with particular focus on north-eastern Greece, suggests growing awareness on this issue.

Thirdly, the order that will prevail in the conflict-inviting area stretching from the Aegean to the Red Sea. Here, Greece’s interest is obvious, since the viability of the Baltic-Aegean axis also depends on the Eastern Mediterranean and Red Sea security to ensure fluent connection with the Indo-Pacific. Hence Greece’s commitment to Egypt’s stabilityPatrick Werr, “EU pledges billions of euros for Egypt as it seeks to curb migration”, Reuters, 17 March 2024., its leading role in the EU’s Red Sea naval mission ASPIDESDerek Gatopoulos, “Greece takes the helm in an EU naval mission in the Red Sea”, AP News, 26 February 2024., and its declared ambition to become India’s gateway to Europe“Greece is India’s gateway to Europe, PM says”, Kathimerini, 21 February 2024. as a link of the India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)“Memorandum of Understanding on the Principles of an India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor”, The White House, 9 September 2023.. Yet, this supposes sustaining a collective engagement in this wide area, which is far from easy“The EU’s Red Sea Security Mission Appears to be Getting Smaller”, <The Maritime Executive, 21 April 2024.. Besides, Turkey’s posture remains a concern. Despite the current lull, Athens and Ankara still struggle to find a mutually acceptable strategic coexistence formula. Indeed, in a scenario that would dramatically increase its leverage on the EU, Turkey seeks to retain control on the connection of both the East-West Middle Corridor and the North-South maritime corridor with Europe. Hence its negative assessment of the IMECRagip Soylu, “Turkey's Erdogan opposes India-Middle East transport project”, Middle East Eye, 11 September 2023. and its poor alignment with EU foreign policy in critical transit areas such as the Eastern Mediterranean, the MENA region, the Red Sea and the Caucasus.

Last and most important, the further development of Alexandroupolis relies on the future of the Baltic-Aegean corridor and, accordingly, on the long-term prospects for Ukraine, Moldova, and Russian-European relations. All remain major unknowns to the day. Another critical element regarding this corridor is the stimulation of a strategic osmosis between Greece, Poland and the Baltic States, who are gaining weight in shaping Europe’s foreign and defence priorities. Greece’s recent accession to the Three Seas Initiative“The 8th Summit and Business Forum of the Three Seas Initiative in Bucharest”, Polish Presidency, 7 September 2023; Robert Schwartz, “What is the Three Seas Initiative and why is it expanding?”, Deutsche Welle, 6 September 2023; “Three Seas Initiative”, Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 14 November 2023., the joint Greek-Polish proposal for a European air defence shieldSotiris Nikas, “Greece and Poland ask EU to create a common air defense shield”, Bloomberg, 23 May 2024. and other initiatives in the military field“Greece – Poland Bilateral Training”, Greek Ministry of National Defense, 25 April 2024. suggest a desire for greater engagement between Warsaw and Athens that may ultimately nurture a stronger common European strategic denominator between parts of Europe who have long shared very different priorities. France’s increasing military engagement in the Mediterranean-Baltic zoneLaura Kayali, “France flexes navy muscles to show Putin (and US) its war power”, Politico, 30 May 2024. may also be interpreted through this lens, as both Greece and France are strong advocates of a European defence pillar – whatever the shape it may finally take.

The port of Alexandroupolis: a strategic and geopolitical assessment

Note de la FRS n°18/2024

Aris Marghelis,

August 1, 2024