Negotiating a FMCT: Still a Priority?

The NPT and the P5 Process

Emmanuelle Maitre,

July 20, 2021

As the Conference on Disarmament (CD) is going to end its session in September 2021 in Geneva, this discussion forum remains plagued by political disagreements that make it dysfunctional. Among the victims of the CD's paralysis, the FMCT project tends to slip off the agenda of some actors who increasingly see it as a lost cause. Yet when UNGA resolution 48/75 was adopted in 1993, the FMCT seemed to be the next logical step in disarmament. In 1995, under the leadership of Canadian diplomat Gerald Shannon, the CD established a working group to negotiate “a non-discriminatory, multilateral treaty on fissile material for nuclear weapons.” From that time on, strong differences emerged on the issue of verification of the treaty. An ad hoc committee was formed in 1998 to address this issue, but by 1999 the CD was unable to agree on a work program. This stalemate was briefly interrupted in 2009, but this did not lead to any substantive work on the subject.

Working groups and draft treaties

In 2014 and 2015, there were positive developments with the creation of a Governmental Experts Group (GEG) that published a draft treaty and identified points of consensus among a broadly representative panel, as well as points of divergence.Group of Governmental Experts to make recommendations on possible aspects that could contribute to but not negotiate a treaty banning the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, A/70/81, 7 May 2015. In 2017 and 2018, a new expert preparatory group was convened. Building on the work already done, it aimed to do a more objective job of listing the different possible options for the treaty, in terms of both substance and form, and to point out their implications.High-level fissile material cut-off treaty expert preparatory group, A/73/159, 13 July 2018.

In 2014 and 2015, there were positive developments with the creation of a Governmental Experts Group (GEG) that published a draft treaty and identified points of consensus among a broadly representative panel, as well as points of divergence.Group of Governmental Experts to make recommendations on possible aspects that could contribute to but not negotiate a treaty banning the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, A/70/81, 7 May 2015. In 2017 and 2018, a new expert preparatory group was convened. Building on the work already done, it aimed to do a more objective job of listing the different possible options for the treaty, in terms of both substance and form, and to point out their implications.High-level fissile material cut-off treaty expert preparatory group, A/73/159, 13 July 2018.

Despite this work, to which must be added the work made by research centres and experts who have proposed in-depth reflections on the content of the treaty and its verification and implementation modalities,See in particular the work of the International Panel on Fissile Material (IPFM), UNIDIR, Belfer Center, SIPRI, VERTIC, PRIF, IAEA or the Oxford Research Group. or the treaty proposals published by States,See for instance the draft submitted by France in 2015, or by the United States in 2006. the FMCT today faces significant challenges. First of all, the blockage of the CD seems likely to persist,Not least because of disagreements over disarmament in a broad sense, the prevention of an arms race in space and the question of negative security assurances. which has led some states to propose an ad hoc negotiating format. However, many States remain attached to the official format, and opening the negotiations elsewhere could lead to the alienation of a substantial number of States.

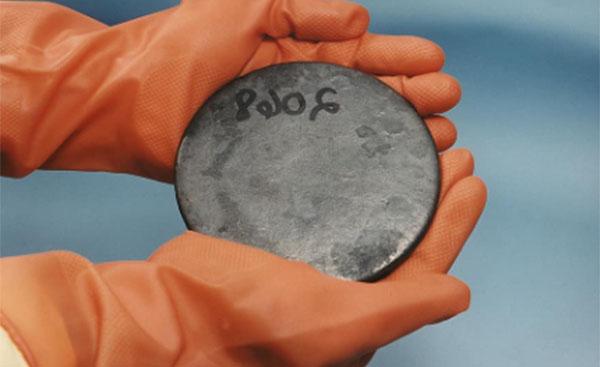

On the substance, the main point of disagreement is the inclusion of existing stocks in the treaty. While the P5 states are opposed to this, Pakistan in particular believes that it is essential in order not to make permanent its inferiority to India, whose fissile material production capacity and stocks are currently greater than its own. Many believe that a form of transparency on stocks would be necessary for the proper functioning of the regime. As such, the issue of verification is also controversial. The Shannon mandate clearly seemed to favour a verified treaty, but in 2006 the United States proposed a draft treaty without verification provisions, deemed to be unrealistic. Since then, the US administration has reversed this position in principle, but there are quite different views on the implementation of a verification system, the mandate of possible inspectors, their nature, and the possible limits to transparency and openness. Finally, there are disagreements about which materials should be banned. Diplomatic efforts have so far focused on HEU for military purposes and plutonium, but several experts have noted the potential value of establishing some form of control over all HEU and other fissile materials to avoid any risk of diversion.

On the substance, the main point of disagreement is the inclusion of existing stocks in the treaty. While the P5 states are opposed to this, Pakistan in particular believes that it is essential in order not to make permanent its inferiority to India, whose fissile material production capacity and stocks are currently greater than its own. Many believe that a form of transparency on stocks would be necessary for the proper functioning of the regime. As such, the issue of verification is also controversial. The Shannon mandate clearly seemed to favour a verified treaty, but in 2006 the United States proposed a draft treaty without verification provisions, deemed to be unrealistic. Since then, the US administration has reversed this position in principle, but there are quite different views on the implementation of a verification system, the mandate of possible inspectors, their nature, and the possible limits to transparency and openness. Finally, there are disagreements about which materials should be banned. Diplomatic efforts have so far focused on HEU for military purposes and plutonium, but several experts have noted the potential value of establishing some form of control over all HEU and other fissile materials to avoid any risk of diversion.

What perspectives for the FMCT?

In this context, and in the face of these obstacles, is it still relevant today to demand and to support the negotiation of an FMCT? At the practical level, fissile material production is currently limited to India, Pakistan, and potentially to Israel or North Korea. The United States, Russia, the United Kingdom and France have all adopted moratoria on the production of fissile material for weapons. China refuses to join the moratorium, but experts generally consider that it no longer produces plutonium or HEU for its weapons.“Countries: China”, International Panel on Fissile Materials, 29 April 2021. Thus, all NPT-designed nuclear weapon states (NWS) are seeking to recycle material to ensure the sustainability of their deterrence. From the point of view of the NWS states, the effects of an FMCT would therefore be relatively limited. It would not be null, however, insofar as it would formalise the moratoria adopted and ensure the irreversibility of the commitments made. Moreover, it could lead, particularly in the case of the United States and Russia, to materials classified as excess being effectively diluted. Thus, this material could no longer be held in storage for potential use to increase the volume of arsenals. Therefore, an FMCT would, in a way, cap the materials available for weapons production. Of course, its value in the area of non-proliferation and nuclear security is more apparent, and it would be, in that sense, a useful complement to the NPT.

At the political level, abandoning the FMCT's objective would be a serious blow to the process of step-by-step disarmament. Indeed, support for the treaty is still regularly expressed, for example by the NPDI in their recommendations to the NPT Review Conference published in October 2020,NPDI Open Letter to the Nuclear Weapon States: China, France, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom, October 2020. or by participants in the Stepping Stone Initiative.Stepping stones for advancing nuclear disarmament, Joint working paper submitted by Argentina, Canada, Finland, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the Republic of Korea, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, NPT/CONF.2020/WP.6, 12 March 2020. For its part, the European Union adopted a decision in 2017 to support the FMCT. The project, implemented by the UNODA, aimed to increase the knowledge of FMCT-related issues among officials, academics, and NGOs from African, Asia-Pacific, and Latin American and Caribbean countries to enable an informed debate at the opening of the negotiations.Council Decision (EU) 2017/2284 of December 11, 2017, to provide support to states in the Africa, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America and Caribbean regions for participation in the consultative process conducted by the High-Level Expert Group on the Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty. We can therefore expect that during the next NPT review conference, probably postponed to 2022, all the States Parties will at least agree on the need to start the FMCT negotiation process as soon as possible.

This paper is part of a series of publications and events organized by FRS to enrich the discussion on the P5 process and on the main issues linked to the NPT and its review cycle. This independent research program is supported by the French Europe and External Affairs Ministry.