The NPT Review Conference: Analyzing the Outcome

The 2015 Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference failed to produce a final document and has been unanimously held as a failure because of major disagreements on nuclear disarmament, the humanitarian consequences movement and the WMD-free zone in the Middle East. This note argues that this lack of success is as detrimental to non-nuclear weapon states as to nuclear-weapon states, and that both groups will need to adopt a more conciliatory attitude if they want to address the rising challenges to the nuclear global order. The positive developments recorded in the Review Conference Main Committee III, dedicated to peaceful uses, are an indication that concrete compromises and trade-offs between the various groups are achievable in the opening review cycle, despite strong political tensions.

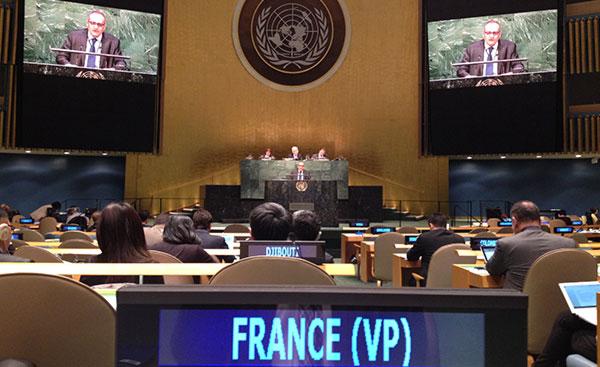

A failure to adopt a final document

In April 2015, at the offset of the 2015 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference, few observers and diplomats were optimistic about its outcome. When it drew to a close on its final day on 22 May 2015, there seemed to be a general consensus on the fact that this gloomy prediction had proved to be right. For many, this failure was especially visible in the incapacity of states parties to agree on a final document.

As soon as the Draft final document was rejected, different narratives were developed to explain this lack of agreement and find a culprit. The United States, the United Kingdom and Canada were strongly criticized for defending the interests of a state not party to the Treaty, since they were the states that eventually rejected the final draft document on the grounds that its reference to a weapon of mass destruction-free zone (WMDFZ) in the Middle East was unacceptable to the Israelis. Egypt, responsible for the controversial paragraph, which relieved the current facilitator of its function, put pressure on the co-sponsors (the United States, the United Kingdom and Russia) to organize a conference before March 2016 and obliged them to invite all states in the region with or without an agreed agenda, was described as unconstructive and focusing on its own political and regional agenda.

For many, the problems ran much deeper than the American-Egyptian divide on the way to move forward on a WMDFZ in the Middle East and were the evidence of a widening gap between nuclear weapon states (NWS) and non-nuclear weapons states (NNWS), especially states linked to the Humanitarian movement Andrea Berger, “Gangs of New York: The 2015 NPT Revcon”, European Leadership Network, 27 May 2015., a gap that the South African delegation described as a new Apartheid Nozipho Mxakato-Diseko, South Africa’s National Statement For The General Debate, NPT Review Conference, 29 April 2015..

Finally, for some, the process was to blame, with important decisions on the future of the Treaty being delegated to the subsidiary bodies instead of being discussed within the main committees, with a lack of clarity and leadership from the Algerian Chair and with a last minute resort to consultations with a small group of states which was denounced by many as undemocratic Tariq Rauf, “The 2015 NPT Review Conference: setting the record straight”, Sipri Newsletter, Essay, 15 June 2015..

A nuanced failure

Apart from these divergences on the reasons why the Conference broke without the adoption of a final document, this consensus on the failure of the Conference is worth noting, because there was none on its goals previous to its opening and different states and groups of states came to New York with different ambitions. Therefore, one could say that the failure is to be nuanced according to these different objectives.

For NNWS, the failure was the most complete. Their goal was clearly to progress on disarmament, and little was achieved in that field. The New Agenda Coalition (NAC), in particular, hoped to fill the so-called legal gap of Article VI, and, with the help of its working paper produced for that purpose, it pushed strongly to adopt effective measures to pursue disarmament within a definite timeframe and through clear benchmarks.

The Non-aligned movement (NAM), in a traditional way, called among other measures for negative security assurances and a support of UN General Assembly resolution 68/32 on a comprehensive convention on nuclear weapons UN General Assembly, Follow-up to the 2013 high-level meeting of the General Assembly on nuclear disarmament..

The Humanitarian Initiative movement, led by Austria, wanted a recognition of the role of the three conferences organized in Oslo, Nayarit and Vienna and insisted on the necessity to acknowledge that new facts had been established, that the danger of nuclear weapons was greater than previously estimated and that it had increased.

Finally, some states, like Sweden, opposed references to preconditions to nuclear disarmament such as a general and complete disarmament (a phrase particularly favored by Russia) or increased stability.

All those demands on the first pillar of the Treaty were strongly opposed by the P5 that pushed to erase them at each negotiation round. They eventually failed to find their way in the Draft final document, whose only new measure on disarmament was the requirement of more precise annual reports from the NWS Lukasz Kulesa, “Five years that will decide the fate of the NPT”, European Leadership Network, 1 June 2015.

The failure was less brutal for the NWS. Before the beginning of the Review Conference, experts and diplomats mentioned several items as main goals for nuclear weapon states, among which:

- Avoiding a theatrical exit of one of the states or a procedural blocking, and it did not happen

- Avoiding further move towards a ban Treaty or the recognition of the validity of the Humanitarian Pledge, and for the time being it has been avoided

- Avoiding a split among the P5, and despite harsh words between Russia and the US, it was averted

- Refusing to agree on unrealistic measures and commitments, by sticking to the 2010 Action plan, which was globally the case.

Several other goals were not achieved by the NWS, but they did not reflect high priorities on which considerable efforts were made, such as a stronger support for the IAEA’s additional protocols, restrictions to the article X or new efforts on nuclear security. One could say that by giving nothing, the P5 received nothing, which raised two questions on the future of the NPT Review Process. First, to what extent did the P5 regret this outcome? Second, is it really detrimental to the nonproliferation regime as a whole?

Two alternative visions

The first thing to examine is whether or not the P5 states are basically satisfied with the way the NPT is working on its three pillars today and are merely trying to preserve the status quo during its review conferences. If the answer is positive, they have little incentive to make compromises, since they neither need nor expect anything in return. Several elements could sustain such a vision:

- the indefinite extension of 1995,

- the ongoing progresses on nuclear safety and security orchestrated by the IAEA and the Nuclear Security Summits, which are rather consensual,

- the progressive resolution of the proliferation crisis with Iran on the one hand, for whom an agreement was found in July 2015, and the impasse of the North Korean dossier on the other hand, which seems so deadlocked that few argue for investing considerable time and energy on solving it, and some even argue that it is no longer a proliferation crisis but a matter of nuclear deterrence.

If we agree to this vision, the failure of 2015 is not a major problem since the Treaty holds and was actually strengthened by the deal with Iran, and since whatever happens with the humanitarian initiative, it does not put into question the implementation of the NPT by NNWS.

Incidentally, it is noteworthy that no Humanitarian initiative states were ready to blow the final draft document themselves, despite their strong distaste for it Reaching Critical Will, “2015 NPT Review Conference outcome is the Humanitarian Pledge”, 22 May 2015, which shows that they still see an interest in retaining the Treaty and bolstering its implementation. In this vision, the NPT would be preserved for some time, the status quo may be maintained for some years, with limited progress on disarmament depending on the international situation, and probably an enduring impasse on the Middle East WMDFZ which could, in the worst case scenario, transform future Review Conferences in replicas of the Conference on Disarmament. So the NPT itself would still be standing but the Review Conference process would have lost all its interest as a debating forum. From the statements and actions taken by all NWS, it seems that this vision is more consistent with Russian and Chinese interests than with the interests of the United States, the United Kingdom and France (P3).

The alternative vision is that nonproliferation is still relevant in the twenty-first century. Nuclear terrorism is still a danger to be countered, the Iranian crisis is not a thing of the past, the situation in North Korea is not acceptable and nuclear weapon states have a global interest in measures such as the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT), increased transparency and cooperation on the reduction of the nuclear threat.

Ways to move forward

This may be the case because new states are endeavoring to become nuclear powers and many of those are going to claim sensitive technologies such as enrichment and reprocessing. After the Iranian deal, the international community will need to think of how to accommodate these demands, which may be legitimate, but will still pose a risk in terms of nonproliferation and nuclear security. Moreover, when the time constraints of the Iranian deal are reached, in ten to fifteen years, Iran will have achieved the status of nuclear hedger – which might already be the case today – and the P3 will have an interest in pushing forward measures intended to strengthen the nonproliferation regime, for instance by increasing verification requirements for states mastering certain technologies like enrichment.

The P3 also has an interest in thinking of creative ways to reduce the risk linked to nuclear weapons in nuclear states, for instance through agreements on doctrines or confidence building measures. As a consequence, nuclear weapon states should not merely try to preserve the status quo or simply limit damage, but should try to convince other states of the relevance of all the pillars of the Treaty and that it should not be abandoned for a new initiative such as a convention to ban nuclear weapons “NPT review: failure underlines challenges ahead”, Strategic Comment, IISS, vol. 21, n°15, 10 June 2015and that additional measures should be adopted to assure its pertinence in the twenty-first century. This would require following on from the 2010 action plan but also going further on some issues such as enrichment and reprocessing, and as early as the 2020 Review Conference.

Work in progress on the third pillar

As mentioned above, the main challenges to the regime in the foreseeable future will probably come from emerging powers developing nuclear technologies that were until now almost the exclusivity of NWS. Some work will therefore be required on the third pillar of the Treaty, devoted to peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Encouraging signs can be read from the rather constructive and hard-working atmosphere of the Main Committee III devoted to this question during the Review Conference.

Even if much less covered in the media than the First on nuclear weapons and disarmament, the Main Committee III, chaired by Ambassador David Stuart of Australia, was able to work on tangible issues and engage in a real debate provoked by an ambitious working paper submitted by the NAM, eventually finding common grounds and agreeing on a final report.

This committee capitalized on steps forward made on peaceful uses during the 2010-2015 review cycle. These progresses have been acknowledged by organizations such as Reaching Critical Will, whose NPT Action Plan Monitoring Report, published in 2014, shows that most actions listed under “peaceful uses” in the 2010 Action plan have been accomplished. Only one was not perceived by the report as implemented at all (giving preferential treatment to NNWS, because of increased cooperation between the NWS and India) and two thirds were considered fully implemented.

Nuclear security and nuclear safety were on the forefront of issues debated during the meetings of Main Committee III, with specific recommendations being made on the improvement of export controls, the reduction in stocks and uses of highly enriched uranium, the universalization of the Convention on Nuclear Safety and other conventions linked to nuclear accidents, fuel cycle management and liabilities, the generalization of the IAEA Action Plan on nuclear safety and the diffusion of best practices and confidence-building measures on the safe transport of radiological material, MOX fuel or radioactive waste. Logically, scientific and technological cooperation was also discussed and several initiatives were welcomed in this regard such as the IAEA Renovation of the Nuclear Applications Laboratories (ReNuAL) project, assistance efforts made by regional cooperative agreements or bilateral and multilateral programs aiming at strengthening nuclear knowledge and expertise worldwide. The final report of the Main Committee III calls on states to increase their funding for such initiatives and puts an emphasis on the role played by the Peaceful Uses Initiative created in 2010 by the IAEA to collect funds and complement the Technical Cooperation Fund.

Close to the public, Subsidiary Body III worked also constructively and developed in its final report interesting ideas to strengthen and improve the review process as well as a few elements of compromise on Article X.

Conclusion

More work on these issues will be necessary going forward, and strengthening the regime in these fields will require additional compromises by NWS on the first pillar of the NPT, including but not restricted to arsenal reductions, change of doctrines and postures and the inclusion of tactical nuclear weapons in arms control talks. To make progress on bilateral disarmament, new issues must be taken into consideration, such as among others missile defense, conventional weapons or new technological developments in talks. The issue of verification, tackled by the United Kingdom and Norway, and more recently by the United States government and the Nuclear Threat Initiative, may show the commitment to global disarmament in the long run. Efforts to restore programs to reduce the nuclear threat, especially in the former USSR, should be made. In the framework of the 2010 Action plan, but also with new inputs, these steps should be debated in groups including NNWS, so that those states may be able to make their voices heard and to give suggestions but also to realize the concrete difficulties linked to disarmament and the technical unfeasibility of some of their proposals. Finally, engaging nuclear states non-parties to the NPT, such as India and Pakistan, to work on confidence building measures and reduce the risk of a nuclear conflict should be seen as a priority, both by NWS and NNWS.

However difficult to make, these compromises will be indispensable if the P5 is convinced that nonproliferation and nuclear security are not things of the past, that new measures need to be adopted and that the Review Conference needs to be preserved as a functional debating forum.

The NPT Review Conference: Analyzing the Outcome

Note de la FRS n°19/2015

Emmanuelle Maitre,

October 7, 2015