The region of Eastern Mediterranean (EM), a meeting point of East and West, of North and South, of the three major monotheistic world religions included, constitutes in geopolitical terms a specific subsystem per se. At the crossroads of three continents, Europe, Asia, and Africa, the geopolitics of EM does not involve only regional actors but also actors placed along antagonistic concentric circles: the United States, the Russian Federation and the European Union. The region is also at the apex of two important geostrategic triangles, formed in the North and North-East with the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and in the South and South-East with the Middle East and the Persian Gulf (in Stergiou, 'Russia's Energy and Defense Strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean', Economics World, Mar.-Apr. 2017, Vol. 5, No. 2, p. 102.).

From 2008 onwards, the security and political order in this subsystem, existing since the onset of the Cold War, collapsed, due to the deterioration in relations between the USA's two most capable regional allies, Turkey and Israel and the continuing fallout of the Arab Spring. It's been replaced by a widening civil war in Syria and a geopolitical rivalry among Turkey, Israel, Cyprus and Greece and between Western countries and the emboldened powers of Russia and Iran.

In the meanwhile, the EU-Cyprus-Greece-Israel energy cooperation was strengthened by Europe's interest in the diversification of routes and sources of gas supplies (EU Second Strategic Energy Review, 2008) and the promotion of the Southern Gas Corridor Strategy (SGC). This strategy, was mostly triggered by the worsening Russia-Ukraine relationship in 2006-2009 and the Kremlin's decision to annex Crimea, legally making part of Ukraine (early 2014).

Chapter I - EU Energy Security: Eastern Mediterranean and Western Balkans Geopolitics intertwined with US/EU-Russia Energy Grounded Rivalry in both Sub-Regions

In the last centuries, there has not been a single moment in which Russia was not looking for an access to the warm ports along its South-Western borders, mainly the EM, in order to find a market for Russian goods and bypass the problem of the freezing of its ports during the winter. This search was quickly turned in a longstanding geopolitical guideline sustaining an asserting policy led by Moscow since the second half of the Nineteenth century, in order to break the Rimland's belt surrounding its Heartland territoryN. C. Spykman, The Geography of Peace', 1944.. Nowadays, the export of Russian goods mainly means the export of energy resources and primary goods.

Without the ability to produce and deliver energy, Russia would not have the status it has today, would not have the same special relationship with EU countries like Germany, nor would it attract the US attention. The use of energy resources as a geopolitical leverage and the role of the State in managing them is President Vladimir Putin's manifesto since his ascent to the Kremlin. As a matter of fact, Putin has sought to ensure full control over the energy sector by nationalizing several private companies and using private ones as 'national champions' in charge of pursuing Moscow's foreign policy. In Russia, energy policy and foreign policy proceed side by sideAlexander Sotnichenko, Former Russian diplomat in Israel and currently Associate Professor at Saint Petersburg State University, School of International Relations, personal communication of Andreas Stergiou, Jerusalem, July 2013..

This is precisely the game actually played by Russia and Israel. With Moscow deeply militarily involved in Syria civil war, Gazprom could be granted a role in Israel's energy industry (involvement in the Leviathan gas site development and participation in Israeli gas exports to EU countries), in counterpart of assuring the safety and security of Israel's offshore gas exploitation infrastructure, as Tel Aviv believes Hezbollah could target it in a hypothetic future conflictFrancesco Angelone, 'Putin's Geopolitical Strategy in the Mediterranean', May 4 2016.. Of course, an agreement is far from being reached because of the EU's intention to reduce Gazprom leverage on its energy balance and US support to this strategy.

The strategy consisting in putting the pressure on every single interlocutor by using the menace of concluding an agreement with another one, thus making the most convenient choice in the most favorable moment, established by the Kremlin, rebuffs EU strategy by reaching a MoU with the Italian company Edison and Greek one Depa, in order to bring Russian gas to Southern Europe.

EU source and route diversification energy strategy, coincides with Washington's long pursued aim of putting an end to Moscow's tactic of using its hydrocarbons exports to exercise economic and political influence in Europe. In that sense, both US and EU favorite the defense-economic alliance, with a well-shaped military character between Israel, Cyprus and by extension Greece, aiming both to replace the strategic depth Israel lost after the termination of the defense cooperation with Turkey, and defend Cyprus's rights and jurisdiction over the maritime areas of the island, denied even while US-company Noble Energy was carrying out exploratory drilling off the island's southern coast. In the same, their cultural heritage has set the foundations of the Western cultural model, while the current political developments, with the widespread unrest in the geopolitical sub-systems of North Africa and the Middle East contribute further to the strengthening of the relations of the three states. However, the geopolitical factor of energy is the one that guarantees the seamless collaborative and allied dynamic in the long-term basisI. Mazis-I. Sotiropoulos, 'The role of Energy as a Geopolitical Factor for the Consolidation of Greek-Israel Relations', Regional Science Inquiry, Vol VIII, (2), Special Issue 2016, p. 28..

Russian – Turkish relations

In response, Turkey turned to Moscow to safeguard its ambition to become a major non-Russian transit route for gas sales to the European markets and a regional energy hub, fueling in that way a new form of US-Russia rivalry in the EM region. Yet, despite numerous agreements in the fields of economy, technology, science, culture, health, and tourism, Moscow never stopped regarding Ankara as a threat and competitor to its interests in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

The Iraq war (2003-2009) and the establishing of a de facto Kurdish state in Iraq, substantially affected US-Turkey relations and precipitated the signing of various energy deals between Ankara and Moscow (also on building a nuclear power plant), designed to enforce Turkey's drive to become a regional hub for gas and oil transits, as well as to help Moscow to diversify supply routes and potentially maintain its dominance on natural gas shipments from Asia to Europe. Ankara permitted Russia's Gazprom to use its sector of the Black Sea for laying the South Stream pipeline to pump Russian and Central Asian gas to Europe bypassing Ukraine and Russia and joined a consortium with the aim to build the Samsun-Ceyhan oil pipeline. This has been coinciding with Gazprom's aims to control the entire value chain on the European gas marketA. Stergiou, ibid, p. 105..

That for, Gazprom's main concern for several years has been that Israel's entry into EU markets would severely undermine the company's market share. In addition, from 2013 onwards, Moscow also revived strong relationship with Egypt, striking agreements on trade, military cooperation and nuclear energy, while Cairo endorsed the Russian approach to resolving the Syrian conflict by preserving the Syrian state, President Bashar al-Assad regime included.

In fact, an additional driving force behind Moscow's gambit to further bolster Assad, was Russia's 25-year agreement with Syria to explore its offshore Block 2 (December 2013), as it is estimated that the existing energy finds in the Levantine Basin extend into Syria's offshore territoryibid, p. 107.. In parallel, Moscow, since the beginning of the Syrian crisis, has gradually augmented its naval pressure in EM, a very sensitive area for NATO, and in August 2013 submitted request to rent the 'Andreas Papadopoulos' airfield near Paphos, Cyprus, although since 2012 Russian naval vessels had been using the Limassol port for refuelingibid, p. 107.. In fact, Cyprus has been a key-component of Kremlin's policy in the region, traditionally declaring its commitment to safeguarding Cyprus's state sovereignty and neutrality in order to avoid the pro-NATO militarization of the island. Cyprus has been developing a close defense cooperation with Russia from mid-1990's onwards.

The Russian-Turkish clash only happened in the Syria war aftermath, and particularly during the 2014 Russian invasion of the Crimean Peninsula, a tactical move that shifted the balance of power in the Black Sea at Turkey's expense, but most importantly changed the whole post-Cold War paradigm of European security. Nevertheless, however important Ankara's collaboration might be, Russia's incentives to get involved in the Syria war by helping Assad regime to remain in power, are very important. Moscow opts to strategically divert the West from Russia's primary interests in Europe, that is in East-Central Europe, retain the domestic prestige it won with the annexation of Crimea, break out of the external siege laid by the West immediately afterwards, by trying to fit into the new global order as a great power, and satisfy its own 20 million Muslim populationibid, p. 111..

The temporary deterioration of Russia-Turkey relations in the aftermath of Ankara's assertive attempt to remind Moscow that is primarily interested in Northern Syria and Iraq, to keep under control the Kurdish separatist activity, by replacing the Assad regime with a Sunni government friendly to its interests, was followed by US mediation in the Ankara-Tel Aviv dispute, aiming at facilitating the pro-Western monetization of EM gas along the lines of constructing a pipeline from Israel to Turkey. Ankara and Tel Aviv finally normalized their fraught relations, mainly because Israel is deeply concerned with limiting Iran regional influence, and Ankara remains on opposing sides with Teheran on the civil strife in Syria.

Israel-Turkey deal, nevertheless, did not prevent the rapid improvement of Turkey-Russia relations in summer 2016, so as to continue the building of the Turkish Stream pipeline, sustain alive Russia's contract to build a nuclear plant in Turkey, and keep collaborating in Syria's war. However, the rapprochement is not a strategic alliance, but rather a cooperation of convenience, it is offering both sides leverage to negotiate with the US/EU the open questions of Ukraine, the refugees’ problem for EU internal security, EU-Turkey relations, and the day after in the Syria waribid, p. 112..

Moreover, Moscow's tolerance towards Ankara's military operation into Syria territory since August 2016 that provokes fury to Washington and increases the tension around strategic issues between Turkey and NATO, aims to encourage a strategic separation between Ankara and Western countries. In addition, the Kremlin, by expanding since 2015 its facility at Tartus, Syria, poses a significant challenge to the Israel-Turkey gas pipeline, favored by the US, forcing a strong word in the energy architecture of the EM by actively introducing pipeline projects like 'Turkish/Greek Stream'.

Russian – Turkish gas pipeline relations.

The TurkStream project, proposed by Russia as a counterweight to SGC – after the cancellation of South Stream in Dec. 2014 -, will significantly impact on the latter's second stage of development. Indeed, Gazprom envisages TurkStream as a system that will consist of two sets of 15.75 billion cubic meters (bcm)/year capacity pipes called 'strings'. The first one, would be essentially dedicated to providing a replacement route for gas deliveries to Turkey once Russia discontinues transit across Ukraine at the end of 2019 and, in effect ceases to use the Trans-Balkan Pipeline through Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria for routine deliveries of some 12-14 bcm/y to Turkish customers. The second 15.75 bcm/y capacity string, would be used to deliver gas to European customers beyond Turkey.

As of late 2017, Gazprom had reached agreements concerning potential development of both: i. a southern route to Italy via Greece-so called 'Greek Stream'-, a revival of the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy (ITGI/Poseidon project), and also a more northerly route, - that might be termed 'Son of South Stream'-, via Serbia and Hungary, aimed at either the monitoring station at Tarvisio in northern Italy or at the Baumgarten hub in Austria. However, these agreements are more akin to initial Memoranda of Understanding than to the kind of final investment decisions.

As a matter of fact, gas routing to the markets is the outcome of a power redistribution in the subsystems of: i. the center-west Balkans (FYROM, Kosovo, Bosnia Herzegovina and Albania), ii. Thrace-Aegean, and iii. Dodecanese-Cyprus, with the Kurdish problem as geopolitical factor triggering intense competition between the international power poles of a. US/EU (Germany and France) and Russia for the control of Middle East and Center-West Balkans, and b. an internal competition among the Western poles of US-Germany and France-Germany for the control of center-west Balkans.

Washington wish the entry into NATO of the above-mentioned countries of Center-West Balkans in close cooperation with France, so as to control Russia's influence extending to the Mediterranean. US practically is indifferent on the solution type applied to the name/identity problem between former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) and Greece, a question that, by contrast, seriously interests Germany which in concert with Russia and Turkey do not favorite any solution of the problem dating already since the early 1990's.

Russian President Putin eagerly manipulates Turkey in Syria war conundrum, so as to guide Erdogan in a dead-end, transforming him into a puppet and, given that US is opposed to Ankara's invasion in Syria's north-west against the Kurdish PYD/YPG, in fact break the south-eastern NATO's flank, the Rimland which make a sequel around Russian Heartland, NATO's ultimate geostrategic target. Turkey, trying to avoid trap in Syria, blackmails NATO in center-west Balkans's society, in Thrace-Aegean and Dodecanese-Cyprus defense and economy, all vital to the US so as to complete the Balkan Rimland targeting RussiaJonhn Mazis, 'To Atheato Geopolitico Paignio se Valkania kai Anatoliki Mesogeio' (The Invesibly Geopolitical Game in the Balkans and Eastern Mediterranean), https://slpress.gr, February 2018..

Chapter II - Strategic alliance between Israel-Cyprus-Greece and Egypt-Cyprus-Greece: gas pipeline projects.

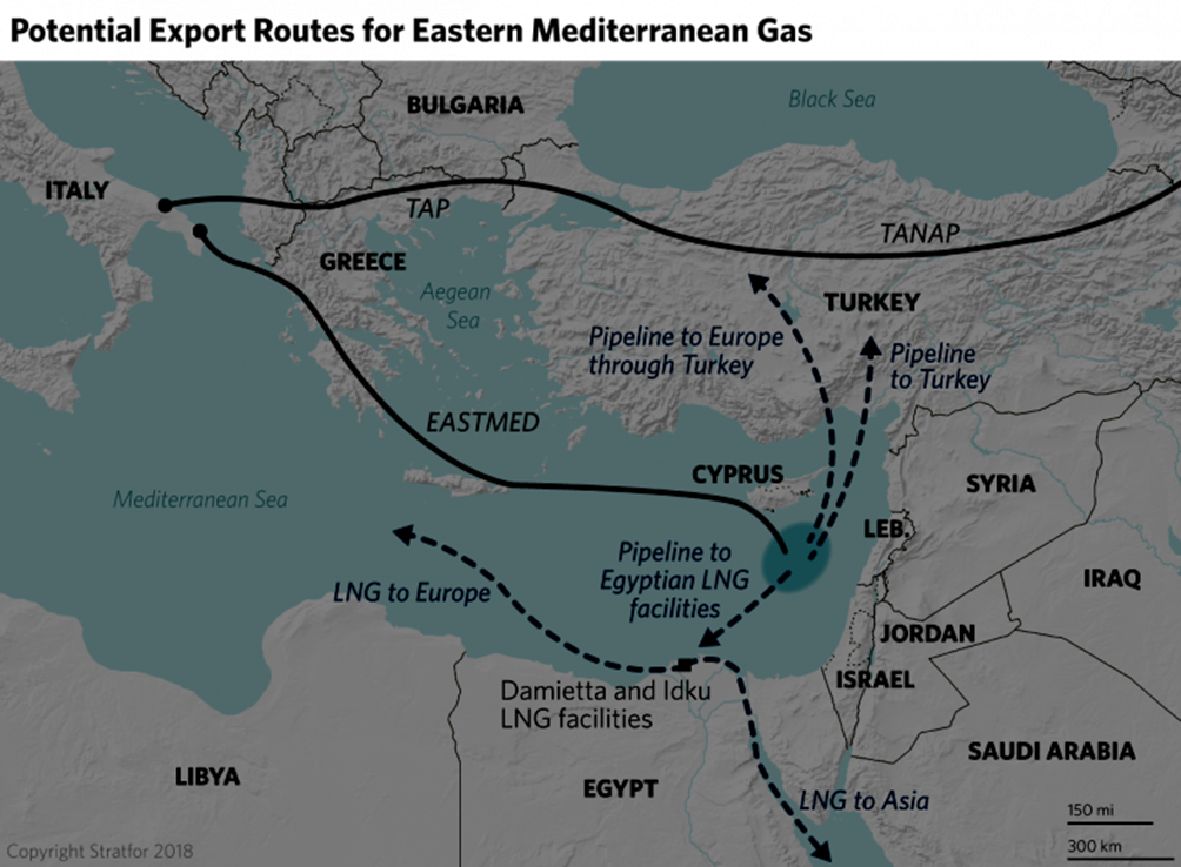

Given that the East Mediterranean region constitutes a credible alternative source with the potential to help EU diversify its energy sources and reinforce its supply and energy security, it would be wise for Europe that the Fifth Corridor of gas (namely the EastMed), is not transported via Turkey, as the Fourth Corridor gas (TANAP and TAP pipelines), otherwise EU energy security will be compromised. Even though a pipeline to Turkey does make economic sense, security concerns that Turkey faces, nullify any economic advantage. Indeed, in Turkey looms the danger of potential internal instability, related to the increasing polarization of political and social attitudes. Namely, the alienation of the country's Kurdish community, bombing attacks in major cities attributed to Islamist militants and the ferocity of the government's post-coup crackdown, which prompt serious concerns in the Western business community about Turkey's internal security situationJohn Roberts (Senior Fellow, 'Atlantic Council'), 'The Turkish Factor', Conference: 'The Future of Eastern Mediterranean Gas', PRIO Cyprus Center, 21 Novemlber 2016..

Furthermore, given that Cyprus, as an EU and Eurozone member, has already proved its usefulness to Europe various fields (including its defense policy), in view of the explosive situation in the Middle East and EU urgent need to combat terrorist attacks, Brussels utterly needs the alternative EastMed energy security advantage for itself. Indeed, Cyprus constitutes the easternmost defense bastion and border of Europe.

The wider Middle East region, characterized by inherent instability in its peripheral geopolitical subsystems (North Africa, Middle East, Near East), is under permanent pressure by Ankara's attempt to implement its 'neo-Ottoman' doctrineFor the neo-Ottoman doctrine, Ahmed Davutoglu, 'Stratejik Derinlik: Turkiye'nin Uluslararasi Konumu', Kure Yayinlari, Istanbul Kure, 2005., which has in store a dominant role in the wider region for Turkey, from the Balkans to the Persian Gulf. The theoretical principles of this policy can be found in Ahmed Davutoglu’s (Turkey's former Foreign Minister) book 'Strategic Depth-The International Position of Turkey' (2001). As a counterweight, after the gradual alienation of Turkey from Israel, Greece, Cyprus and Israel, have materialized in the political, diplomatic, energy and military sectors a strategic alliance backed by both Washington and Brussels.

Developments of such strategic magnitude, affect European affairs and interests, in particular, those of Cyprus and Greece. Both countries are facing since the early 1960's a revisionist Turkish policy applied in the geographic arc from Western Thrace and the northern Aegean down to the south east Mediterranean, in the Cypriot EEZFor an analysis of the Turkish revisionary politics in the South-East Mediterranean, refer to: Ioannis P. Sotiropoulos, 'The Geopolitics of Energy in the South-East Mediterranean. Greece, European Energy Security and the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline'. Contribution in the Roundtable of the International Scientific Workshop 'Repositioning Greece in a Globalizing World', Global and European Studies Institute (GESI), University of Leipzig and the Faculty of Turkish Studies and Modern Asian Studies, School of Economics and Political Sciences, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 8-11 June, 2015.. This policy denies the application of the Lausanne Treaty (1923) provisions' in the wider region, in particular referring to Turkey's borders with Greece, Syria, Iraq and Cyprus.

To deal with this policy, Nicosia and Athens decided to proceed to the built-up of a trilateral/tripartite strategic alliance with Tel Aviv, securing the full support and cooperation of the operationally powerful actor in the southern Mediterranean region, Israel, providing in exchange strategic depth to the Hebrew state and linkage to Europe and “the West”.

So, the three states have created a multipliable power deterministically leading to geostrategic balance, political stability and development in the wider regionI. Th. Mazis, I. P. Sotiropoulos, 'The Role of Energy as a Geopolitical Factor for the Consolidation of Greek-Israeli Relations', Regional Science Inquiry, Vol. VIII, (2), Special Issue 2016, p. 28.. That was utterly demonstrated in the Trilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), signed between the three countries' energy ministers (Nicosia, 08.08.2013), including a clause about cooperation in order to protect key infrastructures (energy and water) in the South-East Mediterranean. Undeniably, the energy geopolitical factor is the qualitative dynamic catalyst in this tripartite allied relationship, impacted by geography, since Israel, Cyprus and Greece have contiguous EEZs, in which large volumes of energy mixture have been, or are expected to be, discovered, and are working on the potential construction of the EastMed pipeline, project of mutual strategic benefitibid, p. 30..

Cyprus-Israel-Greece quasi alliance and the Cyprus problem.

Due to the joint establishment of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between Cyprus and Israel (2010), both countries agreed to a joint extraction of natural gas by the American company Noble Energy. Together with Delek Group, these companies have discovered a reported 26 trillion cubic feet of gas in the Leviathan and Tamar fields. These activities, coupled with the long-running Northern Cyprus Turkish occupation problem and Italian hydrocarbons company ENI drilling for gas in the Cyprus EEZ, have raised the ire of Ankara. Turkey rejects all Cypriot maritime agreements, including those with Israel and Egypt, prompting the latter to voice its support for Nicosia.

Egypt has sought to position itself as a potential gas hub. Its two export terminals, Idku and Damietta, would allow Israel and Cyprus to export their gas without having to construct their own terminals. After having reached an EEZ demarcation agreement (2013), Cairo and Nicosia have agreed to permit producers at the Aphrodite field to use its infrastructure for exports (2016). Israeli authorities have concluded a similar deal, with the prospects though remaining dim due to an arbitration dispute stemming from the cancellation of the previous deal in 2012. So far, the Egyptian industrial group Dolphinus Holding agreed to take 64 bcm from Tamar and Leviathan fields over 10 years. However, no announcement has been made regarding any potential pipelines, and the deal is only referring to the first and smaller phase of Leviathan. Still, the Egyptian option could eventually entice Israel due to the former's proximity and the prospect of sharing infrastructure'The Eastern Mediterranean's New Great Game over Natural Gas', Stratfor, 22 February 2018..

Hydrocarbons discoveries of that scale, have prompted the design of various pipeline projects such as the EastMed pipeline. First proposed by the Greek public gas company (DEPA), having a length of 1,530 km and a capacity of 8 to 12 bcm/y, without the Greek neo-deposits contribution, satisfies EU's goal of multiple suppliers in order to achieve the higher degree of energy security. Passing entirely through European ground and sovereign space, is connected with the ITGI/Poseidon pipeline project that crosses Adriatic Sea to Italy. On December 5, 2017, Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Italy agreed to back the pipeline at a cost of $7.4 billion.

Image 1: 'The Eastern Mediterranean's New Great Game over Natural Gas', Stratfor, 22 February 2018, p. 12.

Image 1: 'The Eastern Mediterranean's New Great Game over Natural Gas', Stratfor, 22 February 2018, p. 12.While the countries expressed hope of signing an intergovernmental agreement on the project in late 2018, no company has yet lent its support to the project on account of critical economic challenges. In addition, Russia, eager to prevent the entry of new large sources of natural gas to Europe, could reduce the gas price to deter investments. Turkey too, could present a political challenge, especially if the EastMed route traverses Ankara's putative continental shelf area.

Nevertheless, in case that the Egyptian government directs the entire quantity of gas from the immense Zohr gas field for domestic consumption, export options towards nearby markets, such as Egypt, are dramatically decreased for Jerusalem and Nicosia. As a result, turning towards further, geographically, markets is unavoidable, a fact that is favorable for EastMed's prospects. Finally, the systemic geopolitical result of the tripartite alliance, which is geometrically accentuated by the energy geopolitical factor and the EastMed project, is the rapid upgrading of the geopolitical status of Cyprus, Greece and Israel on the peripheral level, in the geopolitical system of the southeast Mediterranean among others, and with the warm blessings of the EU.

EastMed will increase EU's energy security, as it is estimated that the Eastern Mediterranean basin contains more than 3.5 trillion cubic meters of natural gas and 1.7 billion barrels of oil'Overview of oil and natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean region', Energy International Organization, August 2013.. This pipeline project on the one hand constitutes a qualitative catalyst in the strengthening and deepening of the allied relationship between Greece-Cyprus-Israel in the long term, and on the other will play a very important role in the transport of energy mix and the increase of EU energy security, while the development of the alliance between Athens, Nicosia and Tel Aviv consists an interalia geostrategic counterweight for the Turkish revisionism in the wider areaI. Mazis-I. Sotiropoulos, 'The role of Energy as a Geopolitical Factor for the Consolidation of Greek-Israel Relations', p. 39..

The hole project was greatly favored by the gas discovery that ENI announced in Cyprus, ('Calypso', 08.02.2018), a find that confirms the extension of the 'Zohr' like play into Cyprus, a reference to the massive Zohr field found in Egypt in 2015. The Calypso discovery makes more likely the development and export of the Cypriot gas, either using the EastMed pipeline project, or in liquefied form as LNG, from an onshore facility or from a floating one. That discovery also brings new players to the picture and new opportunities, and most importantly raises the political stakes for Cypriot gas, in contrary to the unclear political value of the Aphrodite field.

The geographical route of the EastMed, if implemented, is suitable to directly receive the energy production of the Greek neo-deposits, concentrated east of the island of Crete (6 trillion cubic meters of gas and 1.7 billion barrels of oil), via Greek territory, while an important role will be played by the Vertical Corridor project which can vertically connect the Balkan and Eastern European states. Israel's energy reserves (2.5 trillion m3), partly dedicated to export, and Cyprus's reserves (3 trillion cubic meters) mostly destined to export, advocate in favor of the immediate construction of the EastMed pipeline.

Conclusion

The US and Russia, respectively the world's largest and second-largest producers of natural gas, are both poised to play a vital role in brokering (and benefiting) from the coming 'Eastern Mediterranean Game'. On the other side, both regional countries (with or without energy resources) and the European Union interest is to cooperate by utilizing the existing Egyptian LNG infrastructure for the export of EM gas. This would offer flexibility, as connecting offshore gas fields to existing LNG infrastructure could present a 'cheap and quick solution' as opposed to costly and long-term energy infrastructure. It could also provide the first opportunity to test gas cooperation between Egypt, Israel and Cyprus. That cooperation could eventually scale-up in the 2020's should new gas resources be found in the region and should gas demand in export markets justify the construction of additional infrastructure, such as an Israel-Cyprus-Israel pipeline.

For the EU, the materialization of an Eastern Mediterranean gas hub (understood as a crossroads of physical flows, not as a trading platform) based on Egypt’s' LNG infrastructure would be beneficial for both energy policy and foreign policy considerations, providing substance to the long-lasting EU gas supply diversification strategy and functioning as a catalyst for sensible regional dialogue, and most importantly keeping Russia away from acting as a political arbiter for the whole region. Indeed, this scheme’s energy routing to the markets could help EU to avoid becoming hostage to either Russia's monopolistic visions or Turkey's regional aspirations.