Le retour de l’État irakien dans les "territoires disputés"

Observatoire of Arab-Muslim World and Sahel

Arthur Quesnay,

November 26, 2017

Introduction

According to Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution, the “disputed territories” are the territories arabised by the Saddam Hussein regime and claimed by the Kurdish parties in the north of Iraq. Far from homogeneous, this zone is marked by its multi-communal character and spans several governorates with very different political and social realities.The disputed territories regroup the Kurdish, Arab, Turkmen, Yazidi, Shabak Christian and Kaka’i populations spread across the Niniveh, Kirkuk, Salahuddin and Diyala governorates.

In 2003, the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime and the weakness of the central government gave the Iraqi Kurdish parties the occasion to seize a large part of these territories. In the context of the new Iraqi federal government, mixed Iraqi-Kurdish patrols have been established while a shared governance is being developed. This shared governance allows the simultaneous coexistence of Kurdish party institutions alongside those of the Iraqi state. Between 2003 and 2017, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) are increasingly succeeding in imposing a de facto domination by “kurdifying” state institutions. The non-Kurdish populations have no alternatives other than to accept this presence because of the weakness of the central government. Under Kurdish pressure, ethnic divisions shape the new political conflicts in the “disputed territories,” this imposes a hierarchy of identity, whose importance is only increasing within the population. It is becoming impossible to develop economic activities without the support of the Kurdish parties.

In June 2014, Baghdad’s withdrawal due to ISIS gave the Kurds the opportunity to occupy these territories militarily. The weakness of their armed forces, which lost the majority of battles against ISIS, are counterbalanced by massive Western military support which allows them, in fine, to take control. At this time, the Kurdish parties seek to extend their territorial control as far as possible and deepen their policy of kurdification, expelling Arab populations, co-opting Yazidi, Christian and Kurdish militias. The increase of their power in these areas is synonymous with the strengthening of authoritarian and mafia-like circles of power getting the better of state institutions. However, this domination is made fragile by the divisions between the elites of the KDP and the PUK. In September 2017, the referendum on the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan was a way for the KDP to assert itself upon the PUK. By imposing this vote in the “disputed territories,” especially Kirkuk, the former is succeeding in marginalising the latter. This aggressive strategy illustrates the imprisonment of the KDP in a nationalist game of one-upmanship, without taking into account the feedback from important states in the region.

Baghdad’s immediate reaction leads to a major setback for the Kurdish parties who have lost all the contested territories and are isolated regionally. In October 2017, the recovery of the “disputed territories” by Baghdad changed the balance of power in northern Iraq. However, this reconquest relies on a transfer towards militias which do not hesitate to use state institutions for their own benefit. First, this analysis looks at the conditions allowing the quick return of Baghdad to the “disputed territories”. It then describes the consequences for the Kurdish Iraqi political system, on the verge of collapse. Finally, it examines the risks posed by the byproducts of institutionalising militia apparatuses,

1 – The central government’s territorial reconquest

1.1 – The strengthening of Baghdad through the phenomenon of militias

The ideological bubble in which the KDP has confined itself during the referendum is emblematic of its internal functioning where economic interests of the leading class prevail over political goals, and where the instrumentalisation of Kurdish nationalism blurs the understanding of its regional environment. Its ambitions to control “disputed territories” strongly contrast with the absence of structural investments in its economy and the obsolescence of its military apparatus. Relying on the Western support it has benefited from since 1990, the KDP seems unable to measure the current political reforms happening in Baghdad. In the wake of the defeat of the Iraqi army in June 2014, the popular mobilisation created a new nationalist – Iraqi dynamic, providing the state with means to regain control of the whole territory through the establishment of militia networks.

In the Kirkuk Governorate, Shia Turkmens are largely mobilised by paramilitary shia organisations, mostly by the Badr brigades, formed during the Iran-Iraq war Shia militias established in Kirkuk since 2015 comprise the 16 & 52 Turkmen brigades (led by Badr) and the Abbas brigade. Abdul Aziz al-Taei, “Power-Sharing Agreement between Shia Militias and Kurds in Kirkuk”, Al Araby, 22 février 2015; “Amiri from Kirkuk: the Next Press Conference Will Be in Hawija and Charges against the Hashd Are Invalid,” Al Sumaria, 8 February 2015.. Due to the inability of the Kurdish forces to protect the whole territory alone, the PUK is forced to accept cooperation with shia militias deploying in the South East part of the Governorate In June 2014, ISIS captured the subdistricts of Multaqa, West of Kirkuk, and of Taza, South of Kirkuk. This illustrated the incapacity of Kurdish forces to fight by themselves. “Daesh Controls the Building of the Forum and the Police Station West of Kirkuk”, Al Mada Press, 16 juin 2014.. In 2015, this dynamic grew even stronger with the growing number of attacks by the Islamic State, overwhelming the PUK peshmergas. In February 2015, an agreement was signed by the Badr militias and the PUK in order to strengthen their cooperation on the front. This agreement makes the presence of non-Kurdish forces in the Governorate of Kirkuk official Three training camps were created in Taza, South East of the Governorate. Around 5000 fighters are regrouped for the purpose of coming operations against ISIS. In 2017, the number or Shia Turkmen militiamen almost reached 7000. Vivian Salama et Bram Janssen, “Tensions are Rising between Kurds and Shia Militias in Iraq” Business Insider, 17 février 2015.. Local recruitment of Turkmen shia militias in Kirkuk enables them to be largely present in rural areas of the Governorates of Erbil and Suleymanie. In 2017, shia militias represented a well-equipped military force; with a centralised and efficient command, contrasting with the military apparatus of Kurdish parties.

1.2 – The recovery of Kirkuk and “disputed territories”

Following the referendum, the KDP claimed its obvious hegemony on the Kurdish-Iraqi scene and persists in considering itself protected by the presence of the International coalition in its territory. The KDP also relies on its influence within the anti-talabanist trend of the PUK in order to compel its rival to unite under the independentist banner.

However, on the ground, Kurdish parties are badly organised and cannot defend their positions within the “disputed territories”. The collapse of Kurdish forces, on October 15, 2017, can be explained by three factors:

- On the tactical level, there is no coordination between forces of the KDP and the PUK. In order to improve the defense of its territories, each party relies on its security apparatus and multiplies local militia units. Combat units affiliated with the PKK are also deployed by the PUK. The multiplication of these groups worsens the existing coordination issues. Right before the attack by the Iraqi army, there was no global defence strategy for disputed territories.

- Political divides are adding to tactical inefficiency. In the face of the hegemonic strategy of the KDP, the talabanist branch of the PUK has no choice but to ally itself with Baghdad, hoping to retrieve the control it had lost over Kirkuk, with the appointment of a new pro-talabanist governor. On October 15, the PUK forces, maintaining the Southern front, retreated with no resistance to the Iraqi army.

- Kurdish troops are repeating the error they made in 2014 against Daesh. As soon as their first line of defense is defeated, the troops are unable to regroup and thus disband. Peshmergas are coming back to Erbil and Suleymanie in droves. For its part, the Iraqi army, ended up entering without resistance, although its initial focus was on the outskirts of Kirkuk, for fear of being cornered.

In Kirkuk, the Arab and Turkmen inhabitants, who suffered from the arbitrary nature of the Kurdish governance, are now on the streets, cheering for the Iraqi army and Shia militias. The atmosphere of the city is characterised by expressions of joy and the Iraqi flag is being displayed again, after having basically been banned by the Kurds Contrary to the propaganda spread by the pro-KDP media, violence against civilians is limited. Only a few KDP offices are destroyed. Interviews in Kirkuk, October 2017..

In Sinjar, the return of the state also questions its coexistence with the PKK – which filled the space left by the retreating Islamic state. In the framework of its security cooperation with Tehran and Ankara, Baghdad shows its determination not to leave any space that could be a ground for pockets of autonomy. The PKK has been ordered to retreat from any urban space. The Badr brigades and pro-Baghdad yezidi militias are slowly deploying in Sinjar, aiming to control population shifts.

2 – The consequences of the loss of the “disputed territories” for the Kurdish-Iraqi political system

2.1 – The isolation of Kurdish-Iraqi parties

The military and political defeat of Kurdish parties is isolating them at the regional level, while Western chanceries are largely shifting away from what they consider an Iraqi internal issue. Ankara is setting up a security cooperation with Baghdad, especially focusing on the question of the control of the Iraq- Turkey border. Iran, already very present in Northern Iraq, as seen by its training and control of shia militias, is putting direct pressure on the Kurdish parties.

Beyond the military recovery of territories, Baghdad is imposing itself on the Kurdish political system. Several arrest warrants have been issued for Kurdish-Iraqi officials who tried to oppose Baghdad. Kosrat Khasul, a member of the PUK and of the pro-PDK faction, and Najmedin Karim, former governor of Kirkuk, have thus been charged with treason and have been dismissed from their respective offices. In the same way, the rest of the Kurdish political class is threatened.

The 2003 agreements with the Kurds have been scaled down. The 2018 national budget voted on by the Iraqi Parliament now allocates only 12% of the budget to the KRG instead of the 17% initially planned. Moreover, Baghdad no longer recognises the KRG institutions and plans on paying the budget directly to the governorates of Erbil, Duhoc, Suleymanie and Hallabja instead of going through the ministry of finance of Iraqi Kurdistan. This budget allocation by region marks the end of KRG’s preferential treatment. Baghdad thus forces Kurdish parties to negotiate separately their region’s budget, causing a global restructuring of the Kurdish-Iraqi political system.

2.2 – The fragmentation of the Iraqi Kurdish political system

This political reversal challenges the functioning of Iraqi Kurdish institutions. Kurdish parties are cornered and revert to self-centered logics which prove their failure to build common institutions within the KRG. The resignation of Massoud Barzani from his presidential functions does not involve his retreat from the political scene – he remains the president of the KDP – yet it illustrates his party’s shift towards the control over its territories and resources.

The KDP does not have the means to fulfil its hegemonic strategies anymore. Lacking the nationalist emulation to support its populist rethorics, the party has turned back to an authoritarian control of society. Contrary to the PUK, no dissent is allowed within the party. As an example, the debate regarding the succession of Massoud Barzani between his son and nephew is not structured around competing factions, PUK institutions being vertically controlled.

The talabanist branch of PUK must fight in order to keep its monopoly over the party’s administration. This implies the dismissal of pro-KDP officials. With Iran’s support, talabanists hope to control the party and find means for conciliation with Baghdad to negotiate the appointment of a Kurdish pro-PUK governor in Kirkuk. However, the party is losing its electoral base and might not be able to renew its mandate in the 2018 election. Faced with this risk, the party has no option but to take the security path.

3 – The State’s Transfer Towards the Militant Apparatus

The comeback of the state to the “disputed territories” raises the question of the reconstruction of its governing capacities in a context where militias try to take control of the institutions in order to build new political bases. On the one hand, the deployment of the militia apparatus remains centred, because Baghdad pays the wages and approves the appointment of civil servants. The Iraqi army remains the main military actor and militias rely on its logistical support in order to maintain themselves.

On the other hand, the rationale for militia transfer involves many risks and potential abuses. The transfer of responsibilities towards armed groups encourages new networks of patronage. The prospect of the 2018 election favours a politicisation of militia apparatuses and their institutionalisation in order to install a domination at the district level. Their conversion to politics has not yet been confirmed and depends on two factors: the reconversion of militias in state institutions at the district level and the construction of a local base through the co-option of dignitaries.

The return of the State is thus carried out via militant systems in a corrosive dynamic of public institutions. The “disputed territories” are shared between different sectors of control, in which the militants negotiate a “martyr price”, which they claim to have paid during the war, against administrative posts, which allows them to drain the state’s budget. Due to the militants’ monopoly on these institutions, the state can barely rebuild itself. This situation weighs the risk of the presence of a solely military centre against that of a political system under militant control.

The integration of populations into this militia political system depends on the presence of structured political organisations prior to 2014. In the case of Sinjar, the Nineveh plains, and of the Shites Turkmen cities, the presence of communal political parties includes the militant apparatuses and offers them a local anchor. Their relationship to the population grants them a relatively consensual management of governance. After consultation by the parties, the militants chose the heads of the administrations, who are then endorsed by the office of the Iraqi prime minister.

In areas with a Sunni Arab majority, the absence of well-established local organisations post 2003 and the occupation of the Islamic State, have resulted in a low capacity for anchoring militias that are content to co-opt and arbitrarily repress the population, in order to control it. Consequentially, this has had the effect of curbing the return of displaced populations, who would rather stay in refugee camps than suffer abuse by the militias.

Conclusion

The retreat of Kurdish forces from “disputed territories” represents a window of opportunity to strengthen institutions and allow the return of an effective public action to people seeking state guarantees. However, it represents little more than a parenthesis, quickly closed if the independence of the State from the new militant order is not actively supported, particularly by international actors who desire to be included in stabilisation and development efforts in the region.

This situation calls for action at two levels. On one hand, at the political level, through preventive mediation aimed at creating an inclusive type of development, able to integrate rather than to polarise a society which is already heavily fragmented. On the other hand, at the institutional level, through an articulation of the international support towards reform efforts of the Iraqi state.

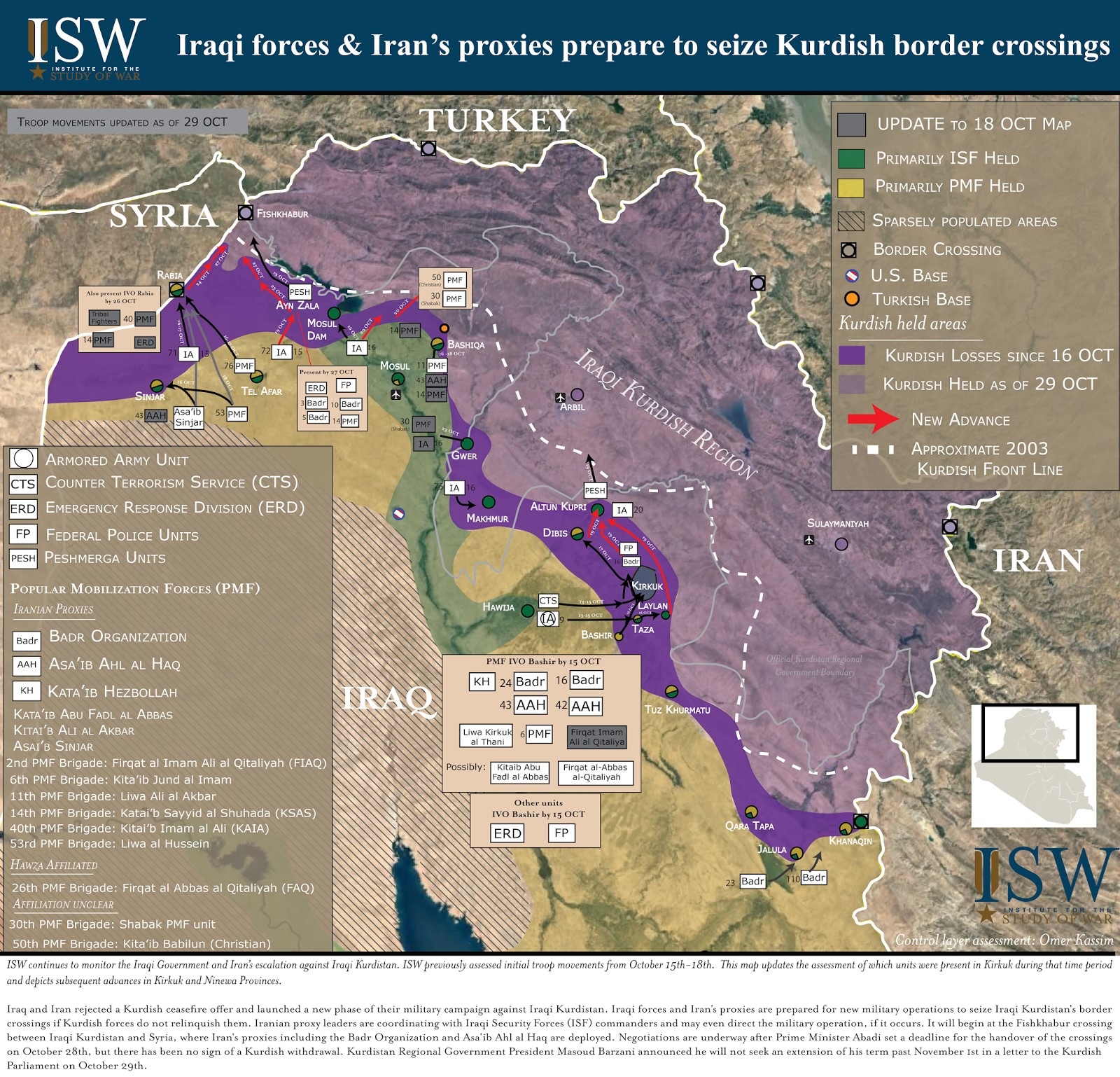

Annexe 1 – Map of “disputed territories”

Le retour de l’État irakien dans les "territoires disputés"

Arthur Quesnay, November 26, 2017