Morocco’s Regional Ambitions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Royal Diplomacy

« Africa must trust in Africa »

H.H. Mohammed VI, Moroccan-Ivorian Forum, 2013

Since coming to the throne, King Mohammed VI has lead a diplomatic offensive in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This has ensured Morocco’s status as one of the best-established North African countries in this region, to the point of Morocco becoming an essential actor. This form of diplomacy is based on classic means such as the development of a network of embassies and consular or economic advisors, as well as the strategy of agreements and alliances towards regional state organizations. However, it also involves diplomacy increasingly reliant upon soft power, especially the religious dimension as well as economic relations. However, security questions primarily concern its neighborhood, marked by the question of Western Sahara as well as frozen relations with Algeria.

1 – An Ancient Anchoring towards Africa

Morocco claims a historical anchoring in Sub-Saharan Africa based on centuries-old relations by means of caravan routes, but also on the historic ties of vassalage between the tribes in Morocco’s Southern territories and the Makhzen (Morocco’s central authority).

These links strengthened after the independences because Morocco was broadly in favor of decolonization in Africa.Notwithstanding the idea of integrating Mauritania into Morocco, as was the case with Western Sahara later on. The suspicion of a hidden Moroccan agenda remained in the hearts and minds of Mauritanians for a long time and did not help any rapprochement between the two countries. The organisation of the Casablanca conference in 1961 is an illustrative example. It was organised under the auspices of Mohammed V whose goal was to establish the foundations of a powerful Africa, freed from colonial domination. Morocco’s founding role within the Organisation of African Unity characterised this African ambition which was not challenged after Morocco left this same organisation in 1984 when the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) was admitted into this African organisation.The OAU, is now the African Union (AU). The SADR, whose government in exile resides in Tindouf (Algeria) campaigns, with Algerian support, for the creation of an independent state. It is the emanation of the Polisario Front (Front for the liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and of the Rio de oro; the names of former Spanish possessions). This opposition lead to a violent armed conflict between 1976 and 1991 between Morocco (who annexed the territory in 1975 with Mauritanian support), Algeria (briefly), Sahrawi armed groups who were armed by Algeria and Libya. Mauritania withdrew in 1979. As of 1991, the question is in the hands of the United Nations, despite Morocco considering it to be closed and the territory as an integral part of the Moroccan nation. The West Saharan conflict, whether violent or dormant, shapes and changes every inter-state relation in the Saharan-Sahel zone.

With regards to the economy, conventions such as “most favoured nation” have been signed since the 1970s with Sub-Saharan countries, such as the DRC in 1972, then successively with Gabon, Niger, CAR, Mali, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Congo and Sudan in 1998. Furthermore, preferential trade agreements have been signed with Senegal in 1987 and with Guinea and Chad in 1997.

Mohammed VI has significantly strengthened Morocco’s African ambitions since his coronation. The monarchy has institutionalised the principle of annual visits to several African countries in order to develop close contacts with Heads of State, but also with the economic and political spheres in almost every country. Moroccan economic diplomacy is no longer satisfied with a simple policy of trade agreements but also relies on the creation of economic networks and direct and personal contacts between Moroccan and African economic actors.

2 – A Permanent Action in Peacekeeping

Morocco has also strived to be a promoter of peace in Africa by intervening in African conflicts as a mediator or participating in peacekeeping missions. For example, Morocco has played a significant role in peacekeeping in Africa. First of all, within ONUC (a UN Mission between July 1960 and June 1964 in the Republic of Congo), but also between April 1992 and March 1993 in Somalia (UNOSOM I), then in the United Task Force (UNITAF) in December 1992. Morocco was then involved with the second UN operation in Somalia (UNOSOM II) from March 1993 to March 1994. Other UN peacekeeping missions have been strengthened by the participation of the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces (RMAF), especially in Angola (UNAVEM II, from 1989 to 1996). In Ivory, Coast Morocco has contributed to the UN operation (ONUCI) since April 4th 2004. In 2007, the RMAF participated in a joint operation between the AU and the UN in Darfur (UNAMID). In the DRC, Morocco participated in 1999 in the United Nations Mission for Peace (MONUC). Morocco was further involved in MONUSCO (United Nations Mission for the Stabilisation of the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 2010 and in MINUSCA in Central Africa. More recently, in 2013, the RMAF intervened in the MINUSMA mission for the stabilisation of Mali.

Morocco can thus be considered to be a moderate actor, contributing to peace between peoples, and such an actor within multilateral bodies. This allows Morocco to develop alliance networks and a reputation as a mediator. This is what some authors describe as a “relational power.”El Houdaigui Rachid, La politique étrangère de Mohammed VI ou la renaissance d’une “puissance relationnelle”, une décennie de réformes au Maroc, Karthala, Paris, 2010.

3 – The Strengthening of a Classical Diplomacy

This form of diplomacy has taken the shape of annual royal tours in Africa. The King of Morocco visits four or five African countries every year: Ghana, Guinea-Conakry, Zambia, Mali and Ivory Coast in 2017; Rwanda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, Madagascar, Zambia and South Sudan in 2016; Senegal, Ivory Coast, Gabon and Guinea-Bissau in 2015; Mali, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Conakry and Gabon in 2014… The recent shift of Moroccan actions towards East Africa is worth noting.

These visits are always made up of a delegation of businessmen and heads of public companies. These visits seek to strengthen bilateral relations with each country (especially in order to influence the African Union and so weaken the Algerian network) and to open new markets for Moroccan firms.

4 – The Offensive towards African Regional Organisations

Morocco’s regional ambition in Africa is expressed in Morocco’s willingness to join the African Union. Following a remarkable diplomatic effort and despite the hesitations of several African countries (including heavyweights such as Algeria, South Africa and Nigeria), Morocco re-joined the organisation in 2017. This was one of the objectives of the annual royal tours in Africa.

Morocco is however developing a policy of rapprochement with the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA). Recently, on February 24th 2017, Morocco applied to join ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States). On June 4th 2017, ECOWAS agreed, in principle, to integrate Morocco within the organisation. Morocco has also come closer to the CEMAC (Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa) with the development of a strategic partnership and the setting-up of a free-trade agreement.National Council for Foreign Trade, 2016, Profil économique et commercial régional de la CEMAC, 2016 Edition.

5 – Tripartite Diplomacy

Morocco is perfectly aware of the advantages its intermediary position between Europe and Africa confers, both in terms of economic development and because of its geographic situation. The tripartite cooperation seeks to help Sub-Saharan African countries benefit from Moroccan expertise by mobilising bilateral and multilateral funding. For example, Morocco has worked alongside the FAO, in the special programme for food security in Niger and Burkina Faso. It is with this goal in mind that King Mohammed VI has announced, during the EU-Africa Summit in 2000, the cancellation of the least-developed African countries’ debts and the lifting of tariffs for these countries’ exports to Morocco.

6 – Economic Diplomacy: Diplomacy lead by the King

Moroccan economic diplomacy is a natural part of Morocco’s development objectives.Amine Dafir, “La diplomatie économique marocaine en Afrique Sub-saharienne : Réalités et enjeux”. Géoéconomie, 2012/4, n°63, pp. 73-83. This involves systematically opening trade markets, increasing exports to the region in order to improve the trade balance especially through trade agreements. It also involves prioritising the standing of Moroccan firms so that they can expand on the international level, using Africa as a base. In order to do so, Morocco has implemented measures to finance trade, whilst promoting the diversification of industrial products. Efforts have also been made to improve transport infrastructure, especially in the aerial sector.

The other aspect concerns the strengthening of Moroccan foreign investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Some studies have suggested that the development of Moroccan FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa has positive effects on Morocco’s GDP.Moubarack Lo, “Relations Maroc-Afrique subsaharienne : quel bilan pour les 15 dernières années ?” OPC Research Paper, November 2016, RP-16-10, OCP Policy Center.

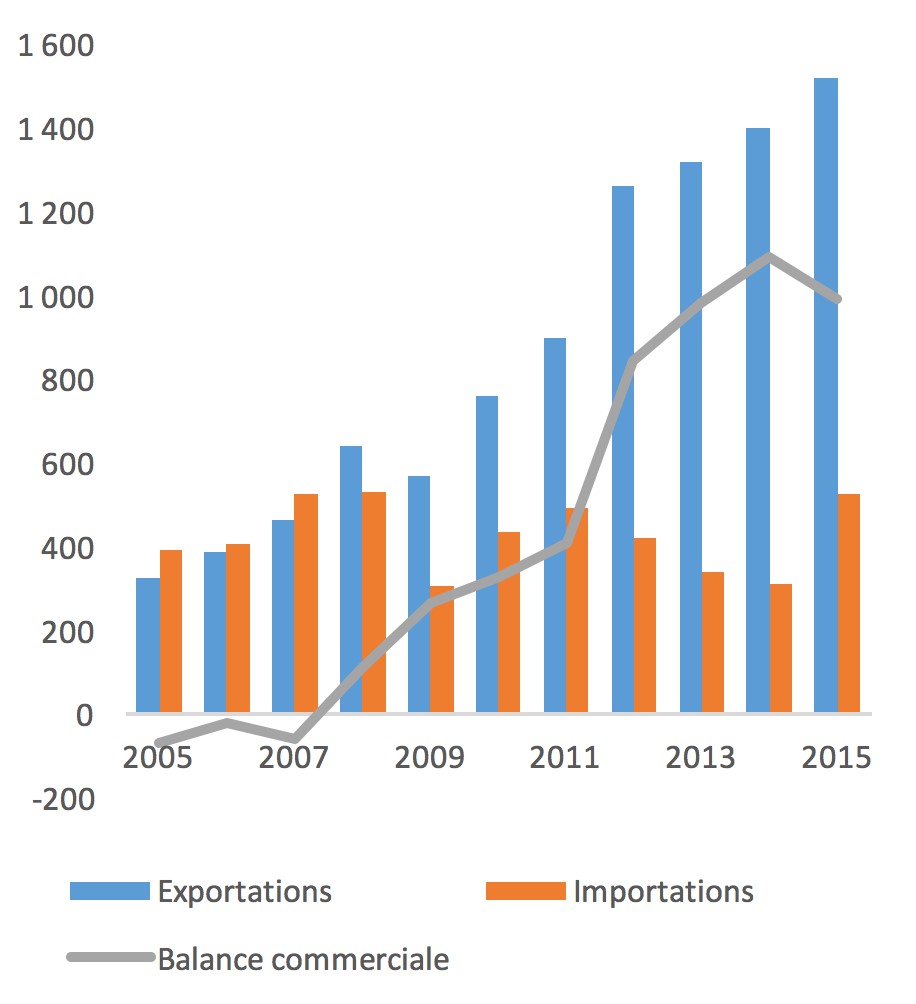

These ambitions have been successful because Morocco is currently considered to be the second largest investor in Sub-Saharan Africa, with South Africa being the first. Trade in goods and services between Morocco and Sub-Saharan Africa has increased by 15% per year between 1999 and 2016. Despite this spectacular increase, it is important to remember that Sub-Saharan Africa has been a limited economic partner for Morocco, responsible for less than 3% of its trade. This being said, it is a growing market which will count nearly one billion individuals in the 2030s. It will, all things being equal, become increasingly important in the future. As of 2008, the trade balance between the two, historically negative, has become positive. Exports to the region have grown by 13% per year, whereas imports have reduced.

This also holds true for Moroccan FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa. Much like in trade, Morocco has reached several investment agreements with these countries, especially reciprocal protection and investment agreements; as well as non-reciprocal tax agreements. Investment regulations and especially FDI limits for Moroccan legal entities have been increased.

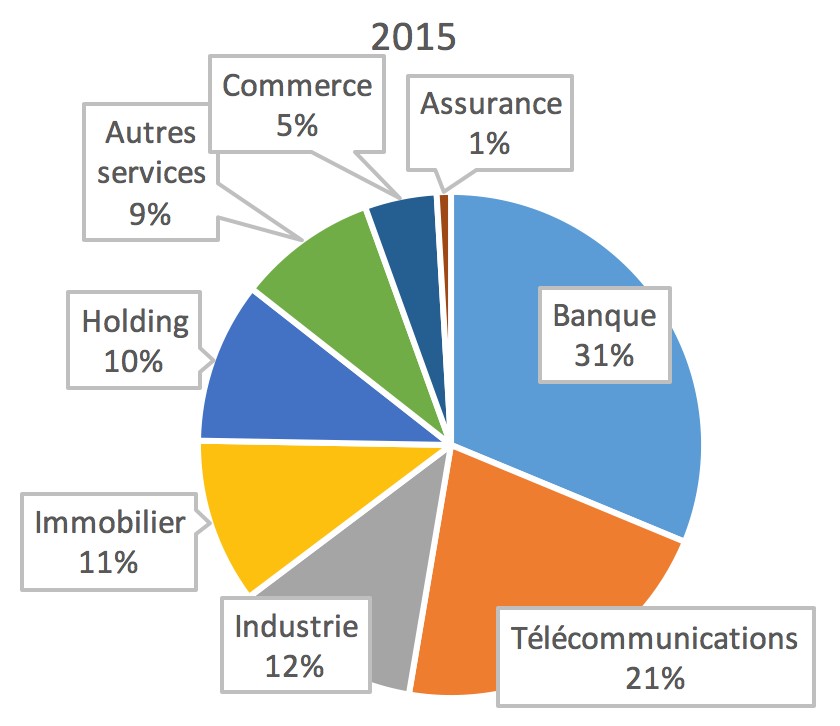

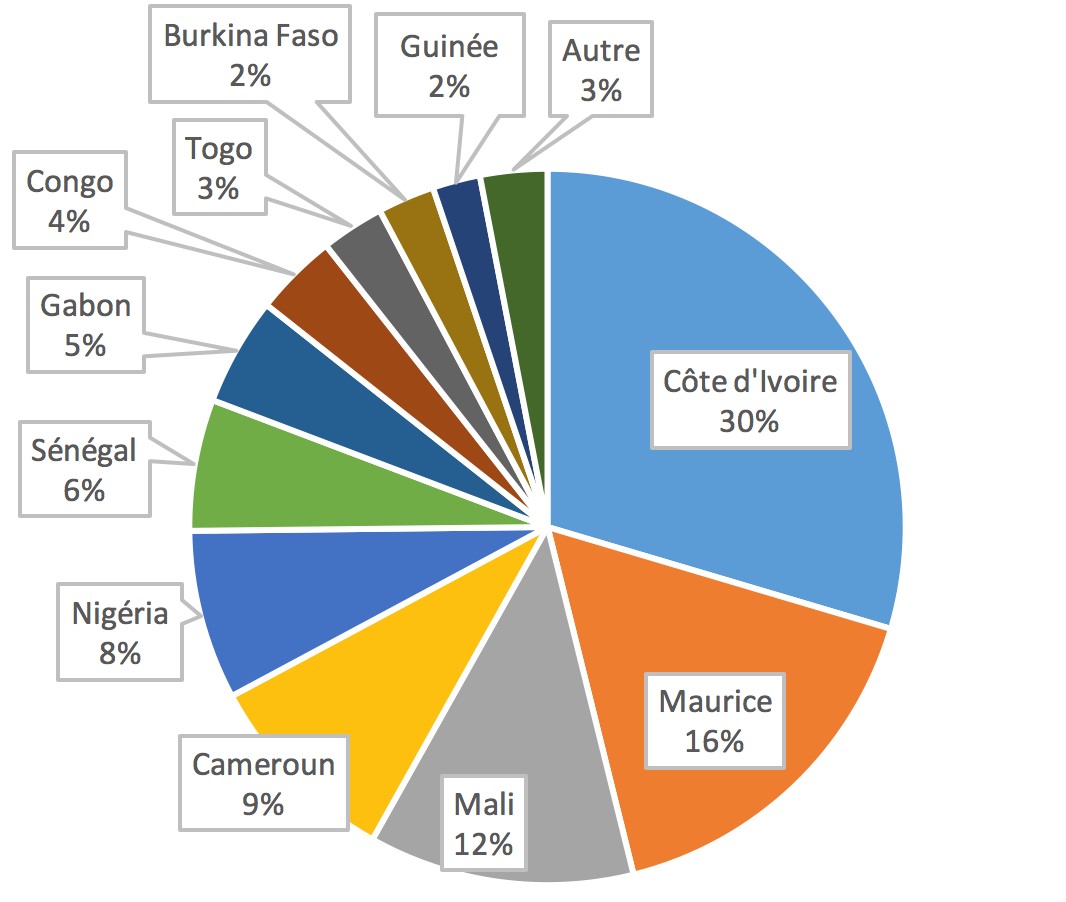

These measures, as well as the ease granted explain the growth of Moroccan FDI, which has increased from $18million to $443million between 1999 and 2014. Sub-Saharan Africa is the primary destination of these flows and represents approximately two-thirds of total flows. Moroccan companies invest primarily in the banking and insurance sector (41% of FDI), as well as telecommunications (35%), holding (10%) and real estate (7%). The countries which receive the most FDI are Mali, Senegal, Cameroon and Ivory Coast.

However, it is difficult to say that the Moroccan private sector is fully aware of the opportunities and stakes Sub-Saharan Africa represents. There is not the same dynamism with regards to official visits in Morocco as there is in Turkey’s private sector and the TUSKON organisation. The process still remains largely dependent on the King’s initiative which drives a policy and drags along a relatively timid private sector. A few large companies working on concrete projects (Attijariwafa bank, BMCE, Maroc Telecom, Sothema, Addoha, Wafa Assurance, CNIA-Saham, Addoba, Alliances, etc.) are the exception however. Large public companies, especially Royal Air Maroc or the National Office of Electricity, are very much involved. For example, RAM has developed 30 flight paths in Africa, with an average of ten flights per day. A gas pipeline project is being discussed with Nigeria.

7 – Religious Diplomacy: The African Influence

of the Commander of the Faithful

Moroccan diplomacy in Africa relies on a unique aspect, the religious dimension which is proving to be just as important as economics. Morocco can use this lever to an even greater effect because many African countries are majority-Muslim and belong to the Maliki School. Further still, Morocco uses its material and spiritual resources represented by the Sufi brotherhoods. These networks are mobilised in order to build close links with numerous partners, whether or not they are close circles of power. Morocco’s religious policy is essentially a form of projecting Moroccan Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa in service of the struggle against the rising influence of Salafism or Hanbali-Wahhabism. The active reanimation of the Tidjanyya brotherhood (whose ramifications cover the Sahel and beyond), via its Moroccan branch (the tomb-mausoleum of its founder is situated in Fez and is one of the instruments used by Morocco in its effort to combat Algerian attempts to rehabilitate the brotherhoods for the same reasons.The President Bouteflika, who is very pious, has also played the brotherhoods card in opposition to the spread of Salafism.

7.1 – The specificity of Moroccan Islam

It is thus important to examine Moroccan action through the perspectives of both the fight against Islamic terrorism but also the definition of a “Moroccan Islam.” Even if this phenomenon has been little studied in the academic field, it is easy to identify what is presented as Islam in Morocco. It is defined by four pillars: the Ashari theological school, maliki rites, Sufism and allegiance to the sovereign.One of the four canonical schools of Sunnism, alongside Hanbalism, shaafism and hanafism. See Chick Bouarame & Louis Gardet, Panorama de la pensée islamique, Sinbad, Paris, 1984, pp. 89-96.

These elements form the coherent pillars of a religious doctrine which seeks to be in agreement with Moroccan society in its current phase of development. The Ashaari school insists especially on the use of Kalam, that is to say dialectical argumentation based on reason. This opens the possibility of rational reasoning and argumentation, and thus, debate. This school accepts plurality of opinion and the relative and contextualised character of interpretations of the dogma. The Maliki rite also develops a culture and spirit of harmony, especially through the significance of the istislah, the general well-being which must prevail on other principles. Hence, the interpretation of dogma, judicial decisions must take into account their impact on society, to the point that some, even if they are fully orthodox, may be abandoned if they lead to social disorder.

The third pillar concerns Sufism. Sufism opens a spiritual space which insists on self-realisation and the conditions for a spiritual realisation for all. All whilst guaranteeing forms of teaching and transmission by qualified individuals who have gone through extensive training before being able to share their knowledge and advice. Sufism further appears as a means of protection in the face of Salafi expansion. It allows opposition to Salafi or Jihadi doctrines by proposing alternatives, especially within zawiyas to those who could be tempted by Islamic jihadism. The final pillar is the importance of the sovereign which entails the reaffirmation of a superior principle confirming the unity of the country beyond political contingencies. This royal prestige is an important element of Morocco’s foreign policy because the King’s word is both an element of protection and commitment.

Thus, there is a structure of governance within Morocco which allows traditional structures to remain alive and present, as well as capable of opposing Salafi institutions and doctrine. Moroccan Islam is implanted institutionally as well as in the country’s foreign policy. This is one of the soft power elements of the Cherifian kingdom which seeks a potential “clientele” of 190 million Muslims in West Africa.

It is in pursuit of this goal that the royal tours in Africa are accompanied by actions favouring the propagation and spreading of a moderate Islam (Islam du “juste milieu”), projection of Moroccan Islam. The King, as the “Commander of the faithful” (Amir al-Mouminine), strives to weigh on the Sahel periphery and even as far as the Red Sea, with the clearly defined goal of opposing radicalism.See Bakary, Sambe, « L’usage diplomatique d’une confrérie : la Tidjaniyya », Politique étrangère, n°4, 2010, pp. 843-854. For the King of Morocco, it’s also about – a goal not widely advertised – combatting Algerian efforts to use the brotherhood for its own benefit (this method is one of the primary axes of Bouteflika’s religious policy). Malikism is his weapon in the face of Salafi Hanbalism.

This message was symbolically confirmed by Mohammed VI during the victory ceremonies in Bamako following operation Serval in February 2014. During this ceremony, he announced his support for the preservation of Mali’s cultural heritage, through restoration of manuscripts, renovation of mausoleums, redynamisation of socio-cultural life and the training of 500 Malian imams in Moroccohttps://revuedepressecorens.wordpress.com/2014/02/25/mali-maroc-les-suites-dune-visite/.

Royal visits are often accompanied by mosque building projects and distribution of donations to religious authorities. The construction or renovation of several mosques is underway in Mali, Guinea, Senegal and Benin. The training of 500 and 600 (according to sources) Sub-Saharan imams is part of this process.

These visits are also an occasion to distribute Qurans, however these versions are edited in Morocco and are different from those distributed by Saudi Arabia and the Muslim World League. The way words are written and readings signs lead especially to an interpretation which conforms to the Warch school (which is more widespread in Morocco) whereas the way words are written in most Eastern copies follows the Hafs recitation school (which is more common in the Orient). The Moroccan edition of the Quran is one of the instruments used to spread an Islam which is mostly dominated by publications from Saudi Arabia and which constitute a distinctive feature and belonging to one doctrinal paradigm rather than another.

7.2 – The creation of transnational religious institutions

Within Morocco, the creation of the Mohammed VI institute for the the training of imams, morchidines and morchidates represents a decisive ambition for its external relations. This is a Moroccan institution with transnational religious ambitions (Baylocq Hloua 2016). This centre allows the welcoming and training of imams from Africa and even Europe in compliance with moderate Islam (“Islam du milieu”, al-wasatiyya). Dozens of French imams have been accepted to these trainings alongside students from most African countries. “Moroccan religious institutions have thus offered to guarantee the notion of ‘spiritual security’ which has emerged side by side with the resurgence within the public space of the notion of a ‘moderate Islam (“Islam du milieu”, al-wasatiyya)’ It is conceived as a mission of public cleanliness, a duty of all citizens under the authority of the Amir al-Mouminine (Commander of the faithful). This task has now been extended to the Muslim neighbours in the South, who have been confronted with turmoil linked to this issue since at least 2012”Baylocq Cédric, Hlaoua Aziz, « Diffuser un « islam du juste milieu », les nouvelles ambitions de la diplomatie africaine du Maroc », Afrique Contemporaine, 2016, p. 257. (Baylocq Hlaou 2016).

In addition to this institution, the Mohammed VI Foundation for West African Ulemas seeks to “unite efforts and methods of collaboration between Moroccan Ulemas and their African counterparts,” in order to promote moderate Islam (“Islam du milieu”, al-wasatiyya), (hence, religious leaders from the Comoros are all trained in Morocco). It is impossible to understate a regional ambition founded on the expression of an Islam which insists on tolerance and moderation. Even if this assertion is challenged by the reaffirmed uniqueness of Islam (islam wahid), including in Morocco, it is a question of participating in social and political stabilisation in the Sahel region as well as in neighbouring African countries in order to contain salafism. This seems to have already been somewhat successful given that President Buhari of Nigeria called for the help of the Moroccan leader of the tidjaniyya zawiya in order to combat the terrorist group Boko Haram.Yabiladi, 10 march 2017.

8 – An African and Sahelian Strategy for Western Sahara and Security

The economy and religion are not the only vectors of Moroccan policy in the Sahel, nor in Africa more broadly.

The Moroccans eventually understood that the “empty chair” policy towards the African Union (AU), since the integration of the SADR in 1984, had proven to be utterly counter-productive. The palace has thus, over the last few years, attempted to reconquer the African political space. This involves convincing African countries of all the negative impacts associated with Sahrawi presence in institutions, but also blocking Algeria, which has made these institutions and the Sahel countries its own exclusive domain. From this point of view, Morocco benefits from the weakening of Algeria’s diplomatic dynamism (which was highly skilled in controlling multilateral institutions), linked to the health of President Bouteflika.Belkaïd Akram, « Objectif Afrique pour le Maroc, une diplomatie tous azimuts », Ramsès 2017, IFRI, Paris. This is expressed in concrete terms by Moroccan mediation (the so-called Skhirat Agreement of December 17th 2015) concerning the political solution in Libya (albeit unfinished), which pulled the rug out from under the Algerians. This activism is further expressed by joining ECOWAS. Finally, Morocco wished to join the G-5 Sahel initiative, however this represents an impassable red line for Algeria.

Alongside Mali, the Kingdom has tried to have it both ways. On the one hand, mediation; first by facilitating a dialogue with the MNLA.See Aït Akdim Youssef, « Maroc : Mohammed VI, L’appel du Sud », Jeune Afrique, 24 February 2014. On the other hand, religion. King Mohammed VI, along with François Hollande, attended ceremonies in Bamako in 2014 celebrating the liberation of Northern Mali. He did so in his capacity as Commander of the Faithful, offering institutional and concrete support of Morocco’s religious capacities in the face of salafist expansion.Ibid.

Finally, “trench warfare” which Morocco and Algeria are involved in (with the Sahrawi question at the heart of the matter) for regional domination is one of the major possible factors of instability in the Sahel-Sahara zone. This “war” disturbs bilateral relations. Relations with Mauritania (with whom Morocco shared Western Sahara between 1975 and 1978) are at the discretion of the coups d’État in Mauritania and often depend on often familial links which successive leaders managed to establish with the SADR and with Algeria. Today, relations are relatively positive (but still marked by tensions) and are expressed by a development of trade between the two countries (facilitated by the opening of the Atlantic road), but equally by the growth of political and security-related exchanges.Simon Pierre, « Le Soft Power de Rabat, l’expansion du Maroc », Cultures d’islam aux sources de l’histoire, p. 14-19.

De facto, Moroccan intelligence and special forces play a key role in this zone. Algeria sees Morocco’s hand behind MOJWA (MUJAO), and vice-versa for other groups. In military and official terms, Morocco, as previously stated, is present in Mali via MINUSMA. This presence is not about to wither.

Conclusion

Concerning the Sahel specifically, and Africa more generally, Morocco is adopting an increasingly radical position. The King’s rhetoric is increasingly marked by anti-colonialism and souverainism (the Riyad speech of April 20th 2016) or the rejection of a Western model considered to be dominant (speech at the United Nations on the 24th of September 2014, read by the Prime Minister Benkirane) and a marked “Africanist” approach (Abidjan speech of February 24th 2014): “Africa is a great continent, by its sharp strength and its potential. Africa needs to take empower itself, it is no longer a colonised continent.”Aït Akim Youssef, « Maroc : le virage anti-occidental de Mohammed VI », Le Monde, 24 April 2016. This diplomacy is thus highly active and supported by a strong economic dimension which characterises Moroccan relations with its southern periphery. The goal is thus to score every possible point both against Algeria, before this giant awakens (if indeed it ever does), but also against the expansion of salafism originating in the Gulf considered to be an imported product and henceforth dangerous. However, it is also a question of presenting oneself as an alternative to the “traditional powerhouses” and not just a simple posture. In the distribution of power in the second half of the 21st century, the Makhzen seeks to play its part - especially in Africa by playing a central role on the continent. In doing so, it places itself, in competition with former sponsors (France, and more cautiously the USA), while avoiding outright conflict, and the “parents” from the Gulf with their aggressive financial diplomacy. This policy puts Morocco in a complicated situation with its “cousins” in the Gulf, whose support it cannot refuse, whilst combatting their proselytism in the Maliki space which it considers to be its natural and historical expansion ground.We can see this in the neutrality shown in the UAE/Saudi Arabian battle against Qatar. Belkaïd Akram, Ramsès 2017, op. cit., p. 218. Good relations which the blunder by Secretary General of the Moroccan Istiqlal, Hamit Chabat, concerning the “Moroccanness (Marocanité) of Mauritania,” in December 2016, did not manage to dent. http://afrique.le360.ma/maroc-mauritanie/politique/2017/01/01/8608-maroc-mauritanie-rien-ne-sera-plus-comme-avant-8608

The remaining question is, notwithstanding the resounding dynamism of Moroccan forms, knowing if the Kingdom will be able to maintain such a policy “by all means" in the long-term, given its limited financial resources.

Finally, the question of relations between the two North African countries is, alongside Libya in recent times, the real problem in the Saharo-Sahelian zone. This hinders development projects, disturbs institutional and bilateral political cooperation, and above all, slows the implementation of a concerted and coherent struggle against armed and radical Islamism in all its forms. To a certain extent, it is possible to say that jihadism benefits, in this zone, from the rivalry between Morocco and Algeria. In any case, it allows it to better prosper. The problem is that it is difficult to see a resolution to this latent conflict in the short or long term. The whole Sahel region will likely continue to feel its effects.

Annex 1: Morocco’s exports, imports and trade balance with Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: WITS and COMETRADE database, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaha-rienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.

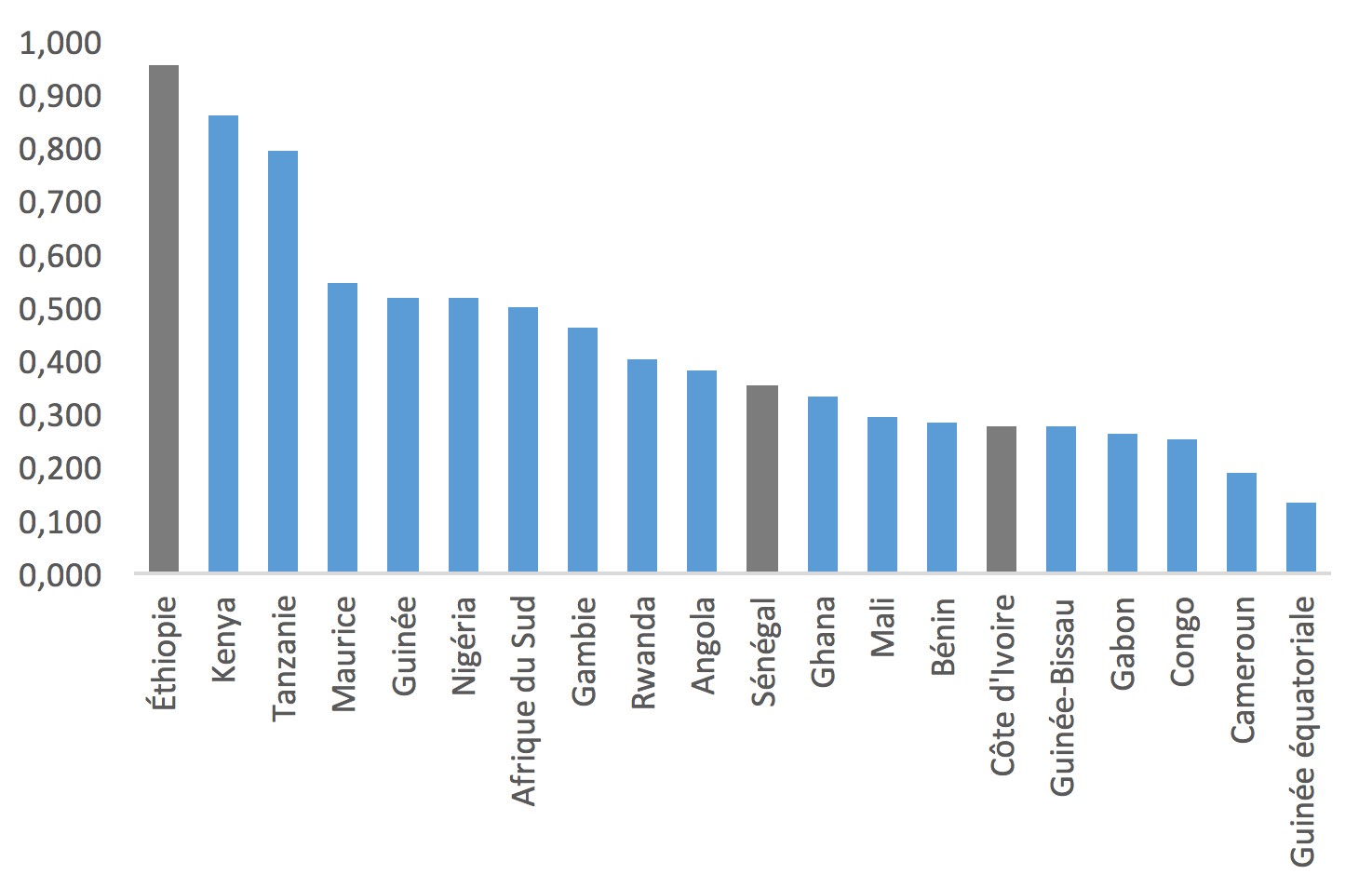

Source: WITS and COMETRADE database, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaha-rienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.Annex 2: Bilateral concentration index of Moroccan exports to Sub-Saharan Africa

Source : CNUCED, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaharienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.

Source : CNUCED, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaharienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.Annex 3: Distribution of the Moroccan FDI flows in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2015 (as a percentage)

Source: Office des changes, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaharienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.

Source: Office des changes, cited in Rim Berahab, « Relations entre le Maroc et l’Afrique subsaharienne : Quels potentiels pour le commerce et les investissements directs étrangers ? », OCPPC, February 2017.Annex 4: Distribution of Moroccan FDI to Sub-Saharan Africa in 2015 (as a percentage)

Morocco’s Regional Ambitions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Royal Diplomacy

Jean-Yves Moisseron, Jean-François Daguzan, October 4, 2017