The Emirate of Kuwait Challenged by Succession

Observatoire of Arab-Muslim World and Sahel

Carine Lahoud Tatar,

September 28, 2018

Introduction

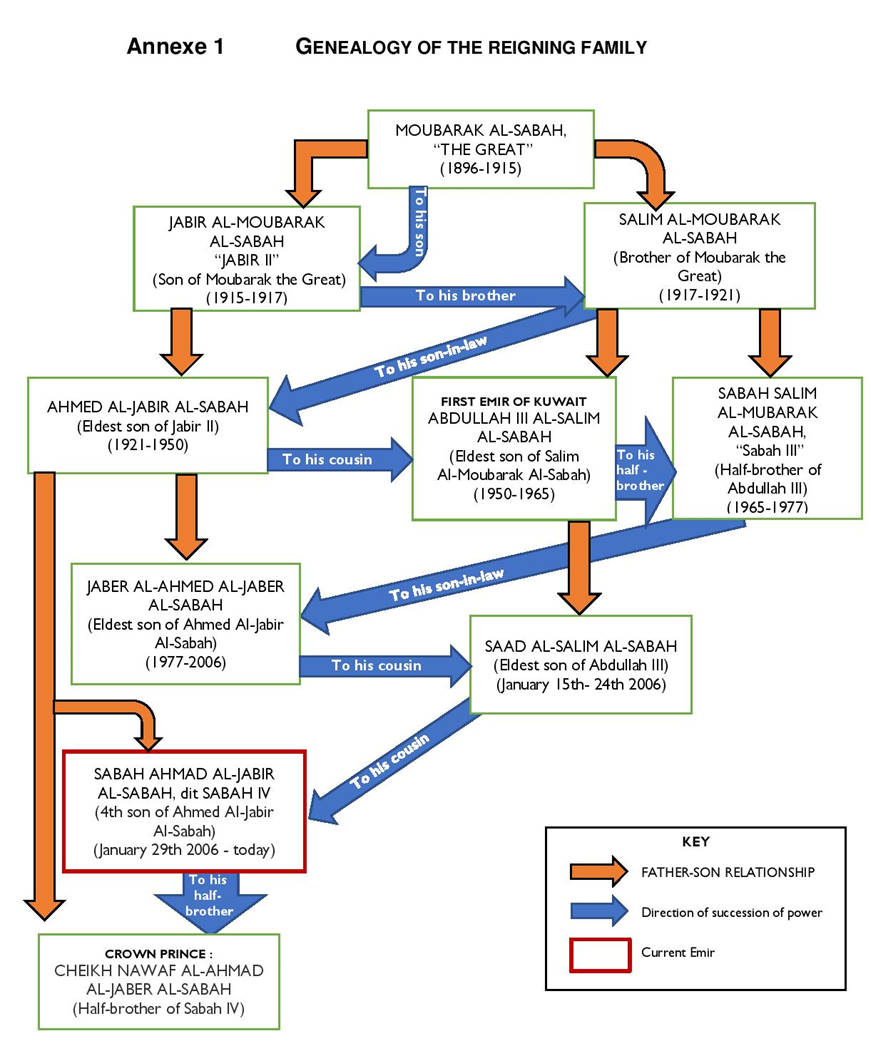

Since the 2000s, the change in political leadership in the Gulf Monarchies has disrupted internal balances in a context of regional crisis, questioning the economic rentier model and profound societal transformations. If the rules of succession vary from one regime to the other, the Gulf Monarchies are subjected to the choice of heir by two systems of selection: the collegiality of Family Council and the respect of the constitutional rules and customs. However, over the past few years, innovations in the matter come one after another: abdication in 2013 by the Emir Hamad al-Thani of Qatar in favor of his son Tamin; rupture of the adelphic tradition in Saudi Arabia in 2017 where the traditional order of succession from brother to brother descended from the direct line of the kingdom’s founder Abd al-Aziz, was left for a vertical transition of power by the king Salman to his son the crown prince Mohamed Bin Salman; and in Kuwait, rupture of the alternance of power between the two cousin branches, the al-Salim and the al-Jabir, in 2006.

In addition, even though the generational transition seems to be in progress in many monarchies on the Arabian Peninsula, as in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Bahrain where the second and even the third generation of princes, the grandsons or great grandsons of the founding father, are in command in an official manner or not, the question rests open in Oman and Kuwait. In Oman, the only monarchy where the sultan Qabous bin Saïd doesn’t have a crown prince and holds together the entire sovereign purse, the appointment procedure of declaring new leadership seems complicated. Likewise, in Kuwait the power transmission scheme resulted in a gerontocracy which feeds political instability and reoccurring institutional blockades, while stirring up inter-dynastic cleavages as well as generational rivalries within the reigning family.

The rules of institutional succession

If the old guard remains at the head of the Kuwaiti state, with a crown prince of 81 years old and an Emir of 89 years old, while the latter (al-Ahmad al-Jabir) fails to arbitrate the quarrels that oppose two of his nephews descended from his direct line, in their race to supreme position, the question of succession, in particular that of generational transmission, becomes a significant challenge. As the rule of primogeniture no longer exists in Kuwait, likewise the order of succession is also excluded, the over abundance of candidates for the throne provokes multiple quarrels within the Al Sabah. To resolve these problems, the reigning family codified the question of succession by giving it a stable legal framework, guaranteed by the 1962 Constitution and the fundamental law no. 4/ 1964 which also defines the status of the crown prince. Thereby, article 4 of the 1962 constitution sets five general rules of dynastic succession: only the descendants of Moubarak the Great can claim the throne; the crown prince must be appointed within a period of a year as of the accession to power of the Emir; his designation becomes effective by decree of the Emir and by the majority vote of assembled deputies in an extraordinary session; in the case where this procedure cannot be done, the Emir submits three names to Parliament among which the latter will have to choose a successor; the crown prince must be over the age of majority, mentally healthy, and the legitimate son of Muslim parents.

Three successional customs with an identical legal strength are added to these formal dispositions. Firstly, to maintain the unity of the reigning family, the competition is determined by the tradition of alternating power between two reigning branches descended from the sons Jabir and Salim of Moubarak the Great (1896- 1915), thus expelling all ambition for power by the lines of his three other sons, Moubarak, Hamad, and AbdallahThe claims of the three lineages, the Abdallah, the Hamad and the Moubarak, are legitimate in the eyes of the 1962 Constitution which does not mention that the crown prince must be descended from the Jabir or Salim branches. Due to their descendance, the princes of the second and third generation can claim the highest positions. This exclusion is justified by the two reigning branches by the fact that, since 1915, the last three have never reigned.. However, this rule is not intangible. It has neither been observed by the al-Salim branch in 1956, when Sabah (1965-1977) succeeded his brother Abdallah (1950-1965), nor by the al-Jabir branch in 2006 when Emir Sabah al-Ahmad (2006-) appointed his brother Nawaf al-Ahmad crown prince. In both cases, it highlights the domination of one line over another at a given moment. Today, the Jabir clan dominates within the reigning family, which leads to the internal tensions of the affected branch and those who are excluded: the al-Salim, al-Abdallah and al-Hamad lines are allies in reducing the preponderant influence of the former.

Secondly, the crown prince is chosen by the Family Council among his peers from the elder generation (in the history of Kuwait, no young prince has ascended to supreme position) and must demonstrate his capacities to lead a state, build a coalition of princes around his person, manage the rivalries within the reigning family and the endemic political crises which are inherent to the Kuwaiti institutional structure, between a weak Parliament often dominated by oppositional groups, and a strong executive at the hands of the Al Sabah. Thus, Kuwait is traditionally governed collegially as a family. It is not a matter of absolute monarchy, but of a dynastic monarchy where the Emir is only the primus inter pares validating the decisions made in family council. Composed of heads of the reigning dynasty’s branches, from the oldest generation, this council is traditionally presided over by the Emir and serves as a private forum of discussion for the princes, leading the house of Al Sabah’s affairs, making important decisions in a collegiate and consensual manner, resolving internal conflicts and managing the distribution of the private income. Finally, the succession is a family affair, a state secret, it is not subject to public debate.

Crisis at the Head of the Emirate: the question of succession and clannish balance

In 2006, the reigning family is threatened with implosion due to power struggles indulged in by the different branches that are able to claim supreme position, the al-Salim and the al-Jabir branch. That which was formally family history, beyond the influence of political games, becomes a national affair.

On the 15th of January, the Emir Jabir Al Sabah dies at the age of 78. The crown prince, Saad al-Abdallah al-Salim, his cousin aged 75 years old, logically succeeds him. But the new leader is nearly as sick as the one he replaced. His health deteriorates rapidly from a colon cancer discovered in 1997, partially paralyzing him (he died in 2008). Severely weakened, the latter cannot give his oath in front of the deputies, as per the provision of article 4, paragraph 3 of the Constitution. Nevertheless, the insistence of the Sheikh wanting to govern plunged Kuwait into an unprecedented political crisis: the Saad clan, supported by Salim al-Ali Al Sabah, chief of the national guard and elder of the reigning family, attempts to pass in force calling on the president of the Parliament, Jasim al-Khurafi, to fix the date of the oath taking. Yet, after having programmed an extraordinary session to permit the new Emir to fulfill his obligations, al-Khurafi made a sudden U-turn rejecting the demand. In fact, the government, under the aegis of the candidate to the throne and the Prime Minister, Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah, in the meantime officially took hold of the Parliament to dethrone the new Emir, motivating its choice with the incapacity of the latter to exercise his constitutional prerogatives on account of the fragility of his health. The Council of Minister’s decision is put forth following an accord between rival clans of the reigning family gathered around the Sheikh Sabah, so that it is he who succeeds the dying Emir, who will have only reigned for ten days. In fact, the 1962 Constitution and the successional law of 1964 put in place mechanisms for deposing the Emir in the case of physical or mental incapacity of the latter to assume his responsibilities. The impeachment procedures and the nomination of a deputy Sheikh are prerogatives of Parliament which must reach an absolute majority decision (the ministers having the right to vote). To get out of this crisis, the Assembly was summoned into an extraordinary session on the 24th of January, and unanimously votes for the deposing of the Sheikh Saad, despite his opposition, who must then relinquish power to the benefit of Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah, enthroned as Emir on the 29th of January 2006.

This political crisis exacerbates the intra-familial tensions between the al-Jabir clan, which the late Emir and his successor are descended from, and the al-Salim clan, represented by the deposed sheikh. The eviction of the latter branch from its ambitions for power will be even more difficult when it is confirmed the following week; in fact, the Emir Sabah nominated his brother, Nawaf al-Ahmad, crown prince, and his nephew, Nasser Mohamed, Prime Minister, both descended from the al-Jabir clan, putting a provisional term onto the dynastic struggles. This change in leadership removes the al-Salim branch from the troika — even though, the monarchical custom presides over the competition with the alternance of power to maintain the unity of the reigning family. The al-Salim branch will be equally excluded from key posts, except for Mohamed al-Sabah al-Salim, keeping the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs and promoted to the post of Vice Prime Minister, as well as that of Salim al-Ali, at the head of the National Guard.

The al-Jabir branch, particularly that of Ahmad al-Jabir’s, descended from the late Emir, dominant today, consolidates its influence on the State. His successor Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah manages to impose himself as the strongman of the Al Sabah, to remove the most influential sheikh, Salim al-Ali, and to silence the opposition. This takeover breaks the reigning family’s facade of unity and revives it’s multiple underlying cleavages: the fractured line between the two branches al-Salim and al-Jabir, which constitute the reigning line, and those that are removed by custom; the second intra-dynastic cleavage brings into conflict the two branches that claim the throne; the third fracture is generational and grows wider between the young princes descended from the third generation³ and the old guard still in command. Finally, since the 2000s, a fourth cleavage has taken shape and positions the princes of the third generationThe third generation refers to that of the great grandsons of Moubarak the Great and descendants from five of his seven sons: Jabir, Salim, Hamad, Abdallah and Moubarak into the succession race. The fragilization of the Al Sabah will incite certain princes to take part in favor of the protest movement of spring 2006. Likewise, the claims from the branches that are traditionally excluded from the alternation resurface, insofar as the customary rules of succession have not been respected.

Thus, the crisis of succession reconfigures the balance of forces to the detriment of the reigning family, weakened by the internal struggles between the different branches, while Parliament comes out smelling like a rose and, in the eyes of many Kuwaitis, becomes the unique guarantor of the country’s stability as well as the defender of the Constitution. Between the two successions, the Parliament played its role of independent constitutional authority. For the first time in the history of the Gulf and of Kuwait, an elected body effectively deposed the monarch and established another, the Al Sabah family having renounced its exclusive control on the succession to the advantage of Parliament, who alone could offer the legitimacy needed by the new Emir. This episode results in the challenging of the balance between the executive and legislative political forces, which favored the former up to this point.

Tensions with the arrival of a new generation of princes

If the institutionalization of political succession rules assured the stability of the Emirate up until now, the rivalries between members of the reigning family took an unseen turn since the rupture of the successional customs in 2006 and the advent of power struggles within the third generation of princes. They center around two principal protagonists: the former Prime Minister Nasser al-Mohamed al-Ahmad (2006-2011), on one side, and his principal rival Ahmad al-Fahd, minister on several occasions, on the other. The first will flatter the Shiites, and the second, from the Awazims tribe and the Popular Bloc of Ahmad al-Saadoun (former president of the parliament and leader of the opposition), close to the Muslim Brotherhood, will gather around his person all the Prime Minister’s enemies, which are the segments of the population disappointed by the general politics of the latter and those opposed to the strategy of rapprochement with the Shiites. Each clan seeks to constitute its own social base and to capitalize on its influence with its elders for political power. The political instability under Sheikh Nasser, with a government that resigned seven times and a Parliament dissolved three times (in 2006, 2008 and 2009), is indicative of a breakdown of the reigning family. Firstly, the oppositional movements since the “Arab Spring” of 2011 will feed on the internal dissent and the conflict will bring the reigning dynasty into opposition with important segments of the population, widening the gap between the regime and society. What is principally at stake becomes the place and the role of the family itself within the political system, in short, its legitimacy as an institutionThe expansion of the political role of the Al Sabah house and its increasing formalization results in the progressively selective centralization of power, monopolizing the top state positions, while uniting within it the elite merchants and tribes. Generally, the key posts return to the princes of the family’s inner circle, so to speak those who are descended from the reigning lines, thus those of the second circle occupy the positions of less importance in the administration and the military. The latter constitutes a recruitment reserve for the state posts. Within the Kuwaiti community, the dynasty distinguishes itself from the other families with six principal characteristics: it possesses a political monopoly on the key posts; it enjoys a social and positional superiority like that of a caste system; its members often receive pensions from their births onward; the rate of endogamy within it reaches 93%; the dynasty has accumulated considerable wealth to transform itself into the principle beneficiary of economic policies alongside the traditional elites; lastly, it enjoys an immunity as public criticism of the family and the Emir is prohibited by the Constitution. Compared to an enterprise that describes its politics and its projects, the reigning family organizes itself according to a hierarchical model of its own. The Family Council is found at the top of this pyramid, resting on a chain of command embedded in the state and the society. To dominate the state machine, the Al Sabah must be able to count as well on the princes who occupy the director positions as on those who position themselves at the intermediate level in the ministries, serving as a relay for decision broadcasts and information networks. To please everyone, the intrafamilial balance is maintained by the gift of key posts to the princes and by the redistribution of the windfall of petroleum. In fact, the principal challenge is to keep hold of unity and of a large internal coalition to preserve its political hegemony. at the head of the Emirate. On the other hand, it seems that the traditional mechanisms of internal conflict regulation within the Al Sabah House are paralyzed and that the Family Council no longer manages to impose itself as an arbitrator of intra-dynastic struggles and a guarantor of internal unity.

The inter and intra-generational antagonisms, long-time state secrets, will make the headlines of the media who has taken part in these internal struggles since the middle of the 2000s. The scandals of corruption and embezzlement, revealed by the princes themselves while implicating their peers, dominate the public debate and feed popular outrage resulting in the storming of the Parliament in November 2011 and the disgrace of the Sheikhs Nasser al-Mohamed and Ahmad al-Fahd in the immediate aftermath. The direct participation of the Sheikhs in parliamentary political games, who are excluded by custom, will boil over into the life of the deputies and even affect the rules of the game and its dynamics. With this context, the Emir will attempt to reform the ranks and create an alliance around his person co-opting the al-Hamad, al-Moubarak and al-Abdallah branches, traditionally excluded from succession, to the disadvantage of the al-Jabir and al-Salim branches. Thus, for the first time in the history of Kuwaiti politics, princes of the marginalized third generation gain access to the inner circle of power: the position of Prime minister returns to Jabir al Moubarak al-Hamad Al Sabah in February 2012, and the sovereign purse such as Foreign Affairs, Defense and the Interior to the secondary lineages. These interfamilial realignment and rebalancing strategies will be confirmed later and ring like a call to order or even a direct exclusion of historically dominant branches, deemed too unruly, whose disputes are beginning to reveal themselves as a genuine obstacle to the stability and development of the country.

Conclusion

While maintaining the promotion of the new generation within the governmental team, the Emir names his eldest son Nasser al-Sabah al-Ahmad (1948-) minister of Defense and vice Prime Minister during the last ministerial reshuffle in December 2017. The influence of the latter also extends to economic affairs: at the head of the superior Council of Planning and Development as well as the Public Function Commission, Nasser is also required to pilot the colossal “Kuwait Vision 2035”Gifted with public financing of a hundred billion dollars, “Kuwait Vision 2035” is blocked by Parliament. In the case of Kuwait City, the project responds to the desire, nay the necessity, of an adjustment after the development of the city following the Iraqi invasion, and therefore aims to construct a city-state that would re-establish itself in the Gulf, and even the Arab world. Kuwait City would launch itself in this way in pursuit of Dubai, on whose path Abu Dhabi and Doha have already committed after certain aspects of their development: the huge size of the Silk City project, with its tower that wants to supplant Burj Khalifa; the importance of the Babuyan Island port and its accompanying free zone, constructed in a style close to the Jebel Ali Free Zone Area; the realization of “Khiran Pearl City” which constructs a marina according to a principle opposite to that of the Dubai “Palm trees” by making the sea enter onto the land with the digging of canals accompanied by the creation of a mangrove, instead of adding strips of land far into the sea. project which aims to develop the country’s infrastructure (Moubarak Port, Silk City, Khiran Pearl City…). The lighting ascension of Sheikh Nasser, minister of the Emir’s diwan (Cabinet) since 2006, strangely calls to mind a certain Mohammed bin Salman appointed crown prince of the Saudi kingdom in June 2017 by his father, King Salman, or even still that of Tamim Al Thani, Emir of Qatar in 2013 following the abdication of his father in his favor.

The Emirate of Kuwait Challenged by Succession

Carine Lahoud Tatar, September 28, 2018