Adam Thiam

September 19, 2017 Download (PDF)

1 – A short history of Malian elections

In July 2018, Mali will organise the fifth presidential election of the so-called democratic era, following the uprisings in March 1991 in favour of political pluralism.

In twenty-six years the country has undergone two fourteen-month long transitions, held seven presidential elections (in 1992, 2002, 2007 where there was only one round, and 2013), as well as eight parliamentary elections and five municipal elections.

If elections were a well-implanted tradition during the colonial era, this method of appointment was bypassed several times between 1960 and 1991 when a communism-prone regime was succeeded by a civil-military dictatorship.

In general, the pre-electoral and post-electoral climates are calm and the loser of the presidential election often congratulates the winner on his victory, well before the official announcement of the results. The 2002 and 2007 elections were exceptions, although there were no calls to violence.

The announcement of the results of the presidential election occurs in two stages, a provisional announcement by the Ministry of Territorial Administration, then definitively by the Constitutional Court.

Finally, the president of the Republic is elected for a five year term, once renewable, according to the wording of the constitution, which has occasionally led to confusion.

2 – The Challenges of the 2018 Presidential Election

2.1 – The security situation

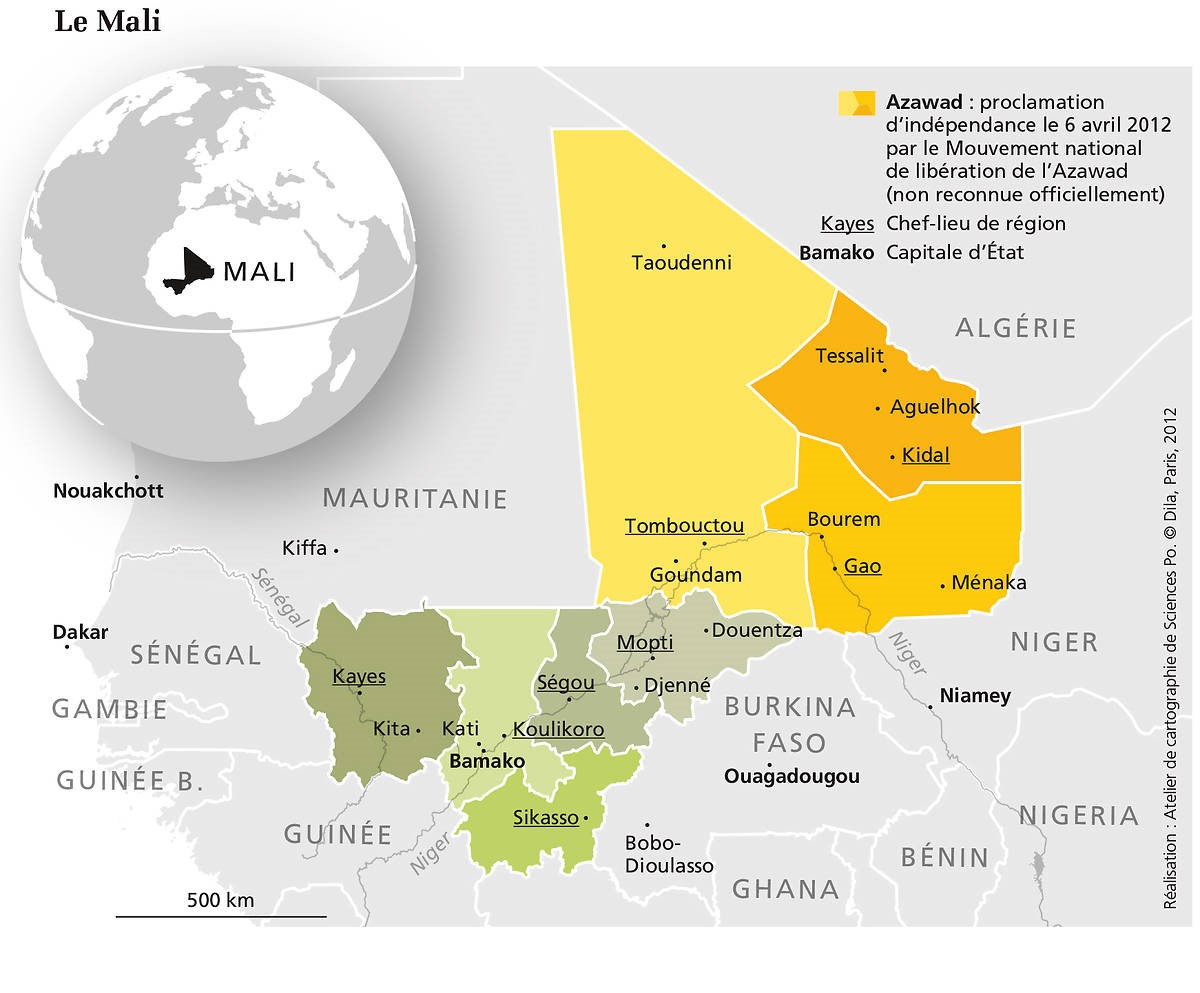

Signs of a severe existential crisis in Mali emerged in 2012. It was a crisis with several fronts, a state crisis, with the resignation of the public authority; an institutional crisis which was worsened by the putsch on March 22nd and by problems restoring constitutional legality. It was also a military crisis with the occupation of the north and the expansion of the separatists of NMLA (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad), of the jihadists of AQIM (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), Ansar Dine and MOJWA (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa) to the centre and the south of Mali; as well as ethnic groups.

Regarding these groups, it is important to mention that as of 2015, the centre of Mali (Mopti region and north of the Ségou region) have experienced constant insecurity linked to:

- jihadist activities, including those of katibat Maasina, led by a Fula preacher named Hamadoun Kouffa

- identity or political claims resulting from the dissatisfaction with public authorities or the army;

- intercommunity conflicts which remained hitherto contained;

- serious crimes (armed robbery and theft of animals).

Be it the north or the centre of the country, there is a rapid decline in stability and social peace, along with a loss of popular confidence in the state and politicians, especially towards the majority party.

2.2 – Jihadist opposition to the democratic election

The greatest risk posed by the remaining insecurity in the north, and increasing insecurity in the centre, is the possibility of jihadists opposing the electoral process during the next presidential election in 2018 (as they did during municipal elections in 2017 which could only be held in 56 towns out of 703, that is to say, less that 10% of all communes in the country).

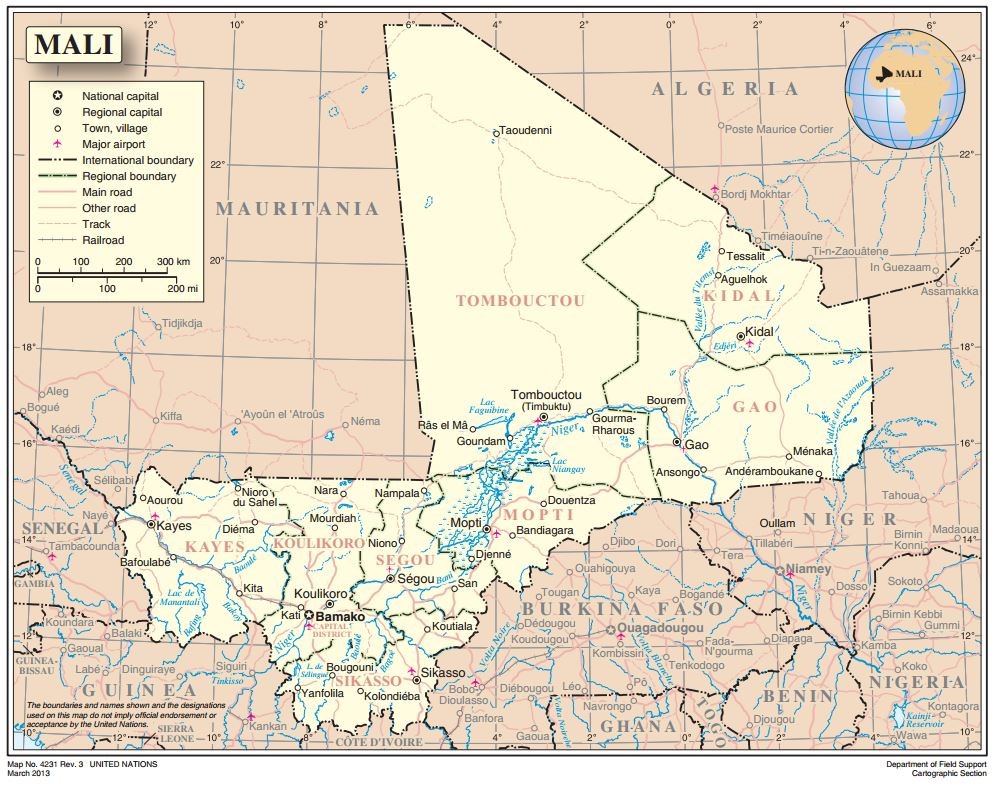

Thus, elections could not be held in the regions of Kidal, Menaka, Gao, Timbuktu, Taoudenit, Mopti and Ségou (see map), precisely where the jihadists had announced there would be no vote for the recent municipal elections.

Yet the scope of insecurity has grown and there has been a worsening of the state’s decline (in its administrative services and security forces) in the north and centre of the country.

2.3 – The barometer of the 2016 municipal elections

Apart from the fact that municipal elections have only been held in a few communes as a result of jihadist threats, the 2016 municipal elections were highly contested both in Bamako and the rest of the country. Reproaches were diverse: inconsistent specimen and ballots (eleven different printing services were given the order), vote buying, challenges to the administrative courts’ decisions, lack of traceability of the single ballot.

The electoral arbitration will be a fundamental element in 2018, with near universal suspicion of what is already known in Mauritania, and based on the Kenyan precedent, as “scientific fraud.” In Mali, the Ante AbanaAnte Abana (Leave my constitution alone) is a platform created to challenge the constitutional reform project of President IBK. It gathers more than one hundred civil society organisations and political parties. It was the driving force of the demonstration on June 17th, of the meeting on July 1st and of the demonstration on July 15th, in which unions and about forty political parties took part, and which put an end to the project. platform, driven by the withdrawal of the constitutional project it demanded of the president, has already made the idea of a “flawless presidential election in 2018” its calling card.

2.4 – The eternal dispute surrounding the electoral register

As of 1992, the Malian political class has challenged an electorate which it judges overestimated when compared to neighbouring countries with a similar population and demographics. Even if the disputes were less heated in 2013, no consensus has emerged on the issue of the electoral issue. The group loyal to the activist Ras Bath,Ras Bath, also known as Mohamed Youssous Bathily, is the most popular organiser of Ante Abana. Initially trained as a jurist, he witnessed the creation of the “Y en a marre” (Fed Up) movement, created in Senegal in 2011 by various artists and journalists to encourage citizens to participate in elections and ensure the respect of democratic rules. The movement played a vital role in ensuring the presidential election occurred under good conditions. Having returned to Mali just before the coup d’Etat in 2012, Ras Bath, radio host and follower of rasta culture, rose to prominence in 2012 by criticising what he saw as the “ambiguities” in the French position regarding the conflict in Mali. With his programme, presented in Bambara, widely popular, especially amongst the youth, he seeks to “raise awareness” and ensure that the people makes his voice heard. Highly critical of those in power, and willing virulent, he doesn’t hesitate to “shock in order to educate”. This attitude has earned him some critics, who criticise him for adopting a populist position and not proposing any tangible solutions. Ras Bath is the son of Mohamed Aly Bathily, Minister of Property Affairs. which advocates for change in 2018, believes that hundreds of thousands of young people don’t have the NINA card required to be registered on the electoral register.

Another opposition party, ADP MalibaADP Maliba, a political party born after the 2012 crisis, held its first congress in 2015 and is since chaired by Amadou Thiam, the youngest member of the National Assembly., is already calling for an independent audit of the electoral register.

Concurrently, the authorities in charge of the register have declared that they are proceeding with its regular update, estimated at this time to be 7,249,350 voters divided between 21,737 polling stations.

2.5 – The cost of the elections

Every election, and especially the presidential election, is very expensive for the Malian state. For example, three by-elections in 2015, cost the state a total of 1 billion FCFA1 billion FCFA = €1.5million, which was heavily criticised by a territorial administration executive.

Despite material support from the UN’s Support to Mali’s Electoral Process Project (PAPEM) and assistance from technical and financial partners, it is the Malian state budget which will have to bear the costs of the presidential and legislative elections planned for 2018.

This is no small challenge, despite the fact that the budget for elections is generally provided for by the state.

In addition to this, one must add the raising of each candidate’s individual guarantee which should increase from 10 million FCFA to 35 million FCFA. Such a high increase, if the measure is applied, will certainly stir up deep turmoil.

2.6 – The religious situation

It is evident that the religious lobby in Mali is special. In 2010, they succeeded in having the Family Code re-read. In 2015, they co-opted a public prosecutor (who happens to be a Christian).

Muslim leaders have also stepped into the breach to put out the recent crisis surrounding the referendum. Even better, in a moment of frustration against Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK), a prominent religious leader threatened to ensure the election of the Muslim candidate at the next presidential election.

A threat to secularity as some consider it, or simple common sense to take into account the popular reality, the question of Islam is an inescapable variable in the 2018 presidential election.

3 – The Candidates

3.1 – The Traditional Candidates

The first is Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, who has implied that he will stand in the election. The activists in his party, the Rally for Mali (RFM) are convinced of it. Without a major shock, IBK will be a candidate. Although his chances of success are less clear than they were in 2013 when he appeared as the natural candidate for more than half the population, the one most skilled to solve Malian crisis. Furthermore, three people within the presidential majority are more than likely to be candidates (Moussa Mara, Me Mountaga Tall, Choguel MaigaMoussa Mara, 42 years old, trained as an accountant, mayor of the 4th commune of Bamako since 2011, was Minister of Urbanism and Urban Policy (September 2013-April 2014), Prime Minister (April 2014-January 2015), the founding president of the Yelema (“Change”) party. Mountaga Tall, 61 years old, is a descendant of El Hadj Oumar Tall, empire builder and religious conqueror, member of the resistance fighting against colonisation, as well as Ahmedou Tall, the King of Ségou. Trained as a lawyer, and figure of the democratic revolution, president of the National Congress for Democratic Initiative (CNID), long-time member of the National Assembly, he was Minister of Higher Education and Research (2014-2017), Minister of the Digital Economy and Communication and government spokesperson (July 2016-April 2017). Choguel Maïga, 59 years old and president of the Patriotic Movement for Renewal (MPR). He was Minister of Trade and Industry from October 2002 to September 2007 and Minister of the Digital Economy, of Information and Communication from January 2015 to July 2016.). Finally, ADEMA has not made a final decision on whether or not it will support IBK from the first round onwards.

It will clearly be more difficult for the presidential camp to transform the political alliance into an electoral alliance with a single candidate. However, the outgoing president remains a strong candidate for he knows the inner workings of the state well. He will face his main rival and leader of the opposition, Soumaila Cissé, whose party is gaining ground, according to the results of the recent municipal electionsSoumaila Cissé, 68 years old, trained as a computer engineer, member of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali (ADEMA), was Secretary General of the Presidency of the Republic (1991-1992), Minister of Finance (1993-2000), Minister of Equipment, Adjustment, of Territory, the Environment and Urbanism (2000-2002), president and founder of the Union for the Republic and Democracy (URD), president of the UEMOA (West African Economic and Monetary Union) Commision (2004-2011) and president of the National Assembly..

But it will be hard for Cissé to be designated as the single candidate of the opposition in the first round. The cohesion shown by the opposition on the platform of Ante-Bana might be fragile.

Modibo Sidibé, like Tiebilé Dramé, to cite just two circumstantial allies of Soumaila Cissé, have previously both been candidatesModibo Sidibé, 65 years old and trained as a jurist, policeman, direct of the cabinet of Amadou Toumani Touré, was president of the Transitional Committee for the Salvation of the People (1991), Minister of Health, Solidarity and the Elderly (1997-2002), Secretary-General of the Presidency of the Republic (2002-2007), Prime Minister (2007-2012). Tjebilé Dramé, 62 years old and President of the Party for National Rebirth (PARENA), former student leader in the opposition to Moussa Traoré, served several terms in prison, was Minister of Foreign Affairs (1991-1992), founder of the newspaper Le Républicain (The Republican), minister of Arid and Semi-Arid Zones (1996-1997) and a former member of the National Assembly. He also served several missions for the UN (especially in Haiti and Burundi), he was the UN mediator during the 2009 Malagasy crisis, negotiator of the peace accords in Ougadougou (June 2013). Tjébilé Dramé is the son-in-law of the former president Alpha Oumar Konaré.. The reasons for these alliances remain quite unclear. Thus, the greatest threat for the opposition would be the scattering of votes.

3.2 – The potential political succession

Moussa Mara, at nearly forty years-old is the most emblematic of these young wolves, even though he did not obtain even 2% of the votes in the 2013 presidential election and despite his under-performance of May 2014 when his visit as Prime Minister of IBK to Kidal resulted in a defeat of the Malian forces against CMA (Coordination of the Movements of Azawad) forces.

IBK’s former Minister of Finance, Mamagou Igor Diarra, is thought to be strongly considering running in the election, and so is the former mayor of Sikasso, Kalifa Sanogo, former director of the mighty CMDT (Compagnie malienne pour le développement du textile) seeking nomination by ADEMA.

In any case, the Macron phenomenon is spreading in Mali and there is a possibility that relatively unknown candidates in the political microcosm will make themselves known, whose age, “moral virginity” and a solid grip in the diaspora will work in their favour.

Conclusion

The 2018 Presidential election is perceived by all actors as a full-scale test of both the democratic maturity of the country (despite the serious breakdown of March 2012) and of the ability of public authorities - and of the international community - to stabilise a state which is surely resilient but strongly affected by insecurity.

All factors influencing the electoral process are of great importance (governance and arbitration of the election, the Islamic situation, the electoral register, etc.) and will be even more important since most of the historical candidates are placing their final bet (most of them will reach the age of seventy in 2022).

However, the major determinants remain the security situation and the ability to hold a presidential election in most of the towns in the following seven regions: (out of twelve in total): Kidal, Ménaka, Gao, Timbuktu, Taoudénit, Mopti and Ségou. These areas are no electoral strongholds population-wise but they are of well-established symbolic political importance.